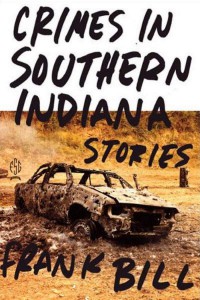

Farrar Straus Giroux made an interesting—and exciting—choice when they published Frank Bill's linked collection Crimes in Southern Indiana. Never known for having crime fiction or indeed for having books about anything other than upper class literature or literature in translation, this first selection of their new fiction line, Originals, fairly screams its difference from the rest of their list.

Farrar Straus Giroux made an interesting—and exciting—choice when they published Frank Bill's linked collection Crimes in Southern Indiana. Never known for having crime fiction or indeed for having books about anything other than upper class literature or literature in translation, this first selection of their new fiction line, Originals, fairly screams its difference from the rest of their list.

Frank Bill lives in rural Corydon, Indiana and subscribes to—among other things—a fairly well-known subgenre of Southern literature called grit lit. Associated at first with Harry Crews (and perhaps tracing its roots a little farther back to Flannery O'Connor) and counting among its membership these days a geographically diverse group of writers including some Appalachian and other regional/rural and crime literature, this ad hoc group is long on place and character and often short on plot. Not so with Frank Bill, whose interest in and love for crime fiction and plot shine throughout Crimes and give his stories a whip-crack sharpness and forward movement many literary writers ought to emulate.

Frank Bill lives in rural Corydon, Indiana and subscribes to—among other things—a fairly well-known subgenre of Southern literature called grit lit. Associated at first with Harry Crews (and perhaps tracing its roots a little farther back to Flannery O'Connor) and counting among its membership these days a geographically diverse group of writers including some Appalachian and other regional/rural and crime literature, this ad hoc group is long on place and character and often short on plot. Not so with Frank Bill, whose interest in and love for crime fiction and plot shine throughout Crimes and give his stories a whip-crack sharpness and forward movement many literary writers ought to emulate.

From the first paragraph of the first story, "Hill Clan Cross," Bill hammers at a reader's attention immediately.

Pitchfork and Darnel burst through the scuffed motel door like two barrels of buckshot. Using the daisy-patterned bed to divide the dealers from the buyers, Pitchfork buried a .45 caliber Colt in Karl's peat moss unibrow with his right hand. Separated Irvine's green eyes with the sawed-off .12-gauge in his left, pushed the two young men away from the mattress, stopped them at a wall painted with nicotine, and shouted "Drop the rucks, Karl!"

The first simile of many to come, those two barrels of buckshot begin to clear away any rogue expectations one might have about what crime fiction bolstered by a healthy dose of the literary looks like. Bill also has a curious habit of dropping subjects from his sentences, which at first confuses, but becomes a sort of on-the-page stutter one can read through and count on to break up the normal rhythms of the sentence and ready a reader for the often jagged plot movement.

It must be said as well that mechanically, these sentences, and thus some of the stories, can be a rough ride. Sometimes clunky metaphors and descriptors adjoin and separate seemingly at random, and otherwise perfectly useful sentences are cut up and refashioned to Bill's purposes of angularity and suddenness. From "Amphetamine Twitch", we see "The bottle of Jim Beam met his lips. Eroded his guilt." Not a bad pair of sentences by any means, but a stylistic quirk that begins to wear after three or four stories.

Another more humorous quirk includes writing in the nomenclature of every firearm a character uses, and there are many. Armaments in Corydon are properly diverse, I'm happy to say, as with many country settings, and with those guns the criminals move the arc of the collection inexorably forward one shotgun blast at a time. I'm just surprised and disappointed nobody drove up in a fucking tank. Despite that shortcoming, and the fact that the awful crimes in the book do occasionally pale when compared with what the news brings daily, Bill makes his characters feel the effects of these guns and those crimes and beyond that, manages to inject his character's stories with an inevitable fate that can, if one is lucky, be kept at bay, but every drug deal gone bad, every jacklighted deer, every senseless murder or horrid sexual crime feels like a small and probably temporary release of the pressure rural life often brings.

Another more humorous quirk includes writing in the nomenclature of every firearm a character uses, and there are many. Armaments in Corydon are properly diverse, I'm happy to say, as with many country settings, and with those guns the criminals move the arc of the collection inexorably forward one shotgun blast at a time. I'm just surprised and disappointed nobody drove up in a fucking tank. Despite that shortcoming, and the fact that the awful crimes in the book do occasionally pale when compared with what the news brings daily, Bill makes his characters feel the effects of these guns and those crimes and beyond that, manages to inject his character's stories with an inevitable fate that can, if one is lucky, be kept at bay, but every drug deal gone bad, every jacklighted deer, every senseless murder or horrid sexual crime feels like a small and probably temporary release of the pressure rural life often brings.

Often, in the middle of a rural nowhere (remember it's always somewhere for the inhabitants, though) there's nothing to do but drink and drug and make up drama. And shoot guns. It's just that Bill's people shoot them in crimes instead of plinking or shooting woodchucks for a quarter apiece. And that sense of the country surrounding the characters actually feels more than inevitable; place is a great weight on all of these characters, and crime is the way Bill's people work off that weight, their means, maybe, of getting attention when the newscasters forgo their jobs and concentrate on the coasts rather than that oft-ignored flyover zone called 'the rest of the country.'

Frank Bill's Indiana is a place I feel deep in my skin now, not for the crime necessarily, but more for the attitude of the characters and the place that claims them, the land where they live. There but for the grace of God go I, pretty much, running slowly in place for my next turn round the earth, somewhere rural with little culture, little desire, and no opportunity to make anything good happen, a place you run from, not to. Close your eyes. Imagine a place like that, and you'll probably remember Able Kirby and Moon Flisport and Knee High Audry, and the other unfortunate folks revealed for our edification and enjoyment so well in Crimes in Southern Indiana.