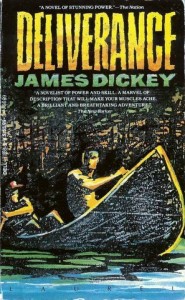

It's clear James Dickey mythologized and often outright lied about the circumstances of his life now, and what's been lost along with his critical reputation is the work, the work, my god the work. Six years of formal education and I was never assigned a Dickey poem, which is a tragedy. A great poet (no reservations), Dickey as novelist, at least as regards Deliverance, unfortunately suffers from the same excess as Dickey the raconteur: mythic potential, slim relation to truth or reality. But that's partly missing the point, too. People who discount the novel or conflate it with the really over-the-top film (squeal like a pig boy, yes yes) are missing out on one of the most interesting and memorable books of the last forty or so years. See what Dwight Garner has to say in the NY Times today on the 40th anniversary of Deliverance.

It's clear James Dickey mythologized and often outright lied about the circumstances of his life now, and what's been lost along with his critical reputation is the work, the work, my god the work. Six years of formal education and I was never assigned a Dickey poem, which is a tragedy. A great poet (no reservations), Dickey as novelist, at least as regards Deliverance, unfortunately suffers from the same excess as Dickey the raconteur: mythic potential, slim relation to truth or reality. But that's partly missing the point, too. People who discount the novel or conflate it with the really over-the-top film (squeal like a pig boy, yes yes) are missing out on one of the most interesting and memorable books of the last forty or so years. See what Dwight Garner has to say in the NY Times today on the 40th anniversary of Deliverance.

On the page and off, James Dickey (1923−1997) was a maximalist. His roomy, loquacious poems spill down the page in a waterfall style and in a voice he called “country surrealism.” It makes sense that he called some of these poems “walls of words,” similar to the record producer Phil Spector’s echoing “wall of sound.” Dickey’s music, rougher and weirder than Mr. Spector’s, was similarly packed with reverb.

It’s odd, then, that Dickey is probably best remembered for a spare novel, one from which he stripped most of the poetry, pulling out the finer phrasings like weeds. That novel was his first, “Deliverance” (1970), a book that turns a youthful 40 this year. It’s a novel that I was happy to discover upon rereading it by a deep lake this summer — Dickey’s stuff is always best read beside a vaguely sinister body of water — has lost little of its sleekness or power. The book’s anniversary shouldn’t slip by unnoticed. More.

You can find Dickey poems all over the internets, including those much-anthologized and little-read pieces Cherrylog Road and The Sheep Child, but take some time and search some other poems out, like maybe Falling, or this one, with the fire in its last lines nearly embarrassing in its sentiment, nearly being the key word.

Adultery

We have all been in rooms

We cannot die in, and they are odd places, and sad.

Often Indians are standing eagle-armed on hills

In the sunrise open wide to the Great Spirit

Or gliding in canoes or cattle are browsing on the walls

Far away gazing down with the eyes of our children

Not far away or there are men driving

The last railspike, which has turned

Gold in their hands. Gigantic forepleasure lives

Among such scenes, and we are alone with it

At last. There is always some weeping

Between us and someone is always checking

A wrist watch by the bed to see how much

Longer we have left. Nothing can come

Of this nothing can come

Of us: of me with my grim techniques

Or you who have sealed your womb

With a ring of convulsive rubber:

Although we come together,

Nothing will come of us. But we would not give

It up, for death is beaten

By praying Indians by distant cows historical

Hammers by hazardous meetings that bridge

A continent. One could never die here

Never die never die

While crying. My lover, my dear one

I will see you next week

When I'm in town. I will call you

If I can. Please get hold of Please don't

Oh God, Please don't any more I can't bear… Listen:

We have done it again we are

Still living. Sit up and smile,

God bless you. Guilt is magical.

How about that??