Best Fiends

All the apparatus at the playground was broken. There was rusted slides, hanging chains without swings, and disassembled monkey bars that looked like crucifixes without a Christ. We rolled out of the sandbox—after we’d shot all the sand and we’d fallen asleep. You had a pail full and a sifter, but that was gone, so we ran. We ran all the way to the fence and then we stopped. It was a pause that lasted a few minutes.

There was nothing beyond that fence, except danger, death and darkness. Then you started to climb; I followed because we rolled like that. I noticed that your legs were as thin as toothpicks, as we’d been running for almost two years now and there was barely anything left of us. You reached the top and jumped down, while I sat there, the wire prongs from the chain links digging into my thighs. “You can make it,” you said, but I knew I couldn’t as beyond that fence there was no hope. I turned my head and looked over my shoulder; behind me was no hope either. I lurched forward and the ground thudded when I hit, my legs were compressed springs, I pitched face-first into the mud.

We had tried, damn, we had tried to clean up. The meetings we went to drunk were all about getting clean and keeping clean. Then we went out again; ended up jobless, in debt with our shorts barely staying up on our hips. We came to this point, on the ground of our playground and then we got up.

After I wiped the mud off my forehead we walked in deeper. It was increasingly dark, the further away we got. “Let’s just lie down for a minute,” you said as the dead angels flapped strongly against the wind, which seemed to channel above us like water in a torrent. “This is how it ends,” you said, as two angels flew down and began to devour us like vultures.

Pole

On our third date Nate took me to a strip club. He was older, the gym teacher with a geology degree and I wanted to appear hip and comfortable—experienced. There wasn’t much for him to do in this town with a geology degree. After I few drinks I had told him and his douchebag friend Slingshot that I had a fantasy of dancing on a stage.

Nate and Slingshot bought me drinks, the fruity kind, as I watched the girls blend into the colored lights. Afterward we stayed and a dancer called Phoenix took me up and showed me how to work the pole. I was down to a tank top and panties when Slingshot said he was hungry and that we should go to the Towne Diner.

Nate had corned beef. Slingshot ordered eggs, a vodka tonic and poked at our forearms when he talked to us. I pushed food around my plate as if it were a pinwheel. “Let’s go,” I said to Nate and Slingshot stayed. He knew someone that worked in the back.

We drove to Nate’s house and the lights were on. I was about to meet his parents. We sat and talked and commented on the news. Nate’s parents wanted to hear the weather so we went upstairs. I was naked when Nate started talking about the Earth, the materials of which it is made, the structure of those materials, and the processes acting upon them.

The Beauty on the Inside

Violet was in her mother’s apron pouch as her mother stood by the stove and stirred the sauce with a wooden spoon. “Hold this,” mother said. Violet felt the heavy weight of it and feared she would topple out of the slick plastic apron and onto the floor, where she wouldn’t be seen. Her mother lifted the top off the pot of broccoli. They looked like trees. She was too small to lift the spoon up to crack her mother on the head with it.

“I refuse to be in anyone’s pocket,” Violet said rebelliously years ago, before she fell out the first time and began life on her own. This was a time she had grown, joined a few armies, spoke to animals, and became educated. She didn’t fall from the sky but she flew and landed in a green forest. It was then she looked out and not up. There was no spoon to hold. Broccoli was just something to eat with a fork and not a big tree needing to be hacked down with a butcher knife.

Violet soon managed short trips—and then vacations. They felt like brief pieces of heaven. She saw the mountains, traveled to cities; even drove a scooter in Rome. After that, Violet went to a small island and felt sand so warm; saw the grains as minute little rocks. She could lie there forever taking time to greet the water. She was married to the ocean but she couldn’t swim; never learned how. The waves reached out, gave her love, and then shrank back, black and menacing, leaving her confused and wanting to drown.

Violet called her mother who told her she was naked on the sofa. Home seemed so casual. She imagined bending down to enter the house and the doors became suddenly taller. She smelled the sauce on the stove. “Put on something for Christ sake,” she yelled. Mother slipped on an apron, which was hung from the mantel, scooped Violet up and placed her inside. It wasn’t until she was reunited with the spoon that she jumped, disappearing like a clove of garlic into the sauce.

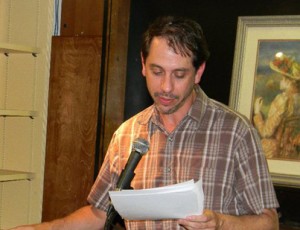

Timothy Gager is the author of ten books of short fiction and poetry. His latest The Shutting Door (Ibbetson Street Press) is his first full length poetry book in over eight years. h He has hosted the successful Dire Literary Series in Cambridge, Massachusetts every month for the past eleven years and is the co-founder of Somerville News Writers Festival.

Timothy Gager is the author of ten books of short fiction and poetry. His latest The Shutting Door (Ibbetson Street Press) is his first full length poetry book in over eight years. h He has hosted the successful Dire Literary Series in Cambridge, Massachusetts every month for the past eleven years and is the co-founder of Somerville News Writers Festival.

His work has appeared in over 250 journals since 2007 and of which nine have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. His fiction has been read on National Public Radio.