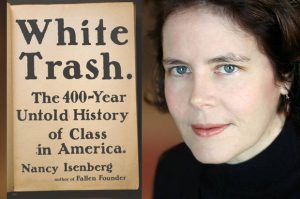

Nancy Isenberg Copyright Penguin/Mindy Stricke

"Americans like the rhetoric of equality but they don’t like it when it’s real."

Nancy Isenberg’s book “White Trash” begins by looking at the characters in “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Both the book and the movie play with the divide between Atticus Finch, who is saintly and proper, and the poor white family, the Ewells, whose daughter’s false rape accusation is at the story’s center, as an example that there are two kinds of white people in the South. The book has been on Isenberg’s curriculum for 15 years, as part of a history class called “Crime, Conspiracy, and Courtroom Dramas,” which she teaches at Louisiana State University.

From “Mockingbird,” Isenberg’s book travels back to the first English arrivals on the American shore, tracing four centuries of how we talk and think about class (and race) in our most unequal union. It’s a bracing, sometimes upsetting read, beginning with its name, a term which still causes deep offense in some quarters.

When did you first start working on the idea of the “poor white” or “poor white trash?”

When you’re a historian, you gravitate toward certain issues. Part of it has to do with my graduate training; my first book dealt with race, class and gender. But it also had to do with when I was working on “Madison and Jefferson,” which I coauthored with Andrew Burstein. I became very aware of the importance of how Jefferson talked about the poor. He has this amazing line where, at the same moment that he’s calling for the education of the poor, something the Virginia legislature would reject, he refers to the poor as “rubbish.” I became interested in figuring out the language: how do Americans talk about the poor? And then I realized that this is connected to the larger problem Americans have about class, that they believe a myth. We are told over and over again by writers, sometimes journalists, but mainly politicians, that we are an exceptional country, that we embrace the American dream. And what’s that rooted to this idea that we believe in social mobility. And we think that that idea, that promise, goes all the way back to the American revolution, that at that moment we broke free from the British system and that somehow we unburdened ourselves from the English class system. Now this is a problem that Americans have – they often prefer the myth over reality.

I began to look more closely at how Americans talk about class. There are a long list of slurs and of terms such as waste people, vagrants, rascals, rubbish, lubbers, squatters, crackers, clay-eaters, degenerates, rednecks, and of course, trailer trash. And you’ll see that just by paying attention to the words people use … what comes up over and over again, is the way the discussion of class throughout our history has forced on the centrality of land and land ownership, as well as what I call breeds, or breeding. And both of these big concepts come from the British. For example, the early indentured servants, the poor who the British wanted to dump into British colonial America, they were called waste people. And where does that term come from? It comes from the idea of waste land.

If a rich field, a productive field, is the sign of success, then fallow and untilled soil, soul that is ignored, the scrubby, swampy, completely worthless tract of land, is what waste land was. We forget – through most of our history we were an agrarian nation. That means that land ownership was the most important marker for designating an individual – and course we’re talking about, primarily, men – it was the most important signifier of civic identity, it was the first way to measure who had the right to vote, it also was a measure of independence. Americans didn’t believe everybody was free, you were only free if you had the economic wherewithal to control your destiny and where did that come from? It came from owning land.

More at: