Chris Tusa thinks so, and makes his case in the Spring 2011 issue of Story South.

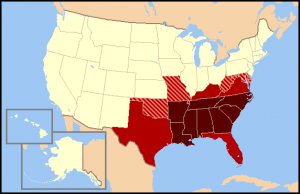

Anyone who’s spent any length of time living in the south knows that history is important to us. In the south, we cling to words like “tradition” and “heritage.” If you search the term “Deep South” on Wikipedia, you’ll find headings like History, Civil War, and Reconstruction. The recent debate concerning the Confederate battle flag only further demonstrated this, immediately prompting the construction of southern-based websites with titles like “Preserving the Southern Heritage” and “History not Hate.”

So why is this? Why, as southerners, are we so obsessed with the past? Is there something hidden in our redneck genes, something wriggling deep in our southern-fried DNA that causes us, as southerners, to cling to the past? One answer might be that as southerners we are so obsessed with the past that we simply aren’t interested or concerned with examining our present or our future. Some might even argue (mostly northerners I presume) that it’s precisely this kind of backward thinking, this constant looking to the past, that has led to the south’s obvious lack of progress, especially in terms of education, pollution, unemployment, and poverty. Regardless of your opinions one way or the other, it’s difficult to ignore the fact that these days young southern writers seem inexorably drawn to the south’s past, rather than its present. Over and over, young contemporary southern writers seem much more content to drudge knee-deep through the south’s bloody history than explore its present. And, when they aren’t exploring the south’s past, they seem much more compelled to rewrite great southern literary traditions than explore the south’s present, or even its future for that matter. Who can forget Susan Lori Parks’ wonderful tribute to Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying or Alice Randall’s rethinking of Mitchell’s Gone with The Wind. Don’t get me wrong. These are all wonderfully creative and skillful books, but as a southern writer in my thirties, I cannot help but wonder why such writers aren’t as equally concerned with examining the south’s present. More.

I think Tusa's essay (by the way, I read his book Dirty Little Angels and really liked it) hits me in some ways–the search for the new, however you find it, and in whatever time period–ought to be a primary goal of good regional writing, for instance. Not being from the South myself, I feel hesitant to say what I think of the thing in its entirety except to list books and writers I've read that argue against his view–Silas House's Clay's Quilt, the stories of Paula K. Gover, who no one seems to care about but me, Amy Greene's Bloodroot and so many more–doesn't really address the point. There are other names I could add and anthologies and books closer to home and among my friendslists I could suggest, but I see his point overall and don't want to distract, though my instinct is to kick against the idea. I do think Tusa could expand his reading, though.

I apologize if the rest of you saw this essay already, but I thought it worth mentioning here. I'm away from the computer for a few days and so won't approve comments until probably Saturday or so, but have at it if you like and I'll do the best I can to approve quickly.

.