Chris Tusa thinks so, and makes his case in the Spring 2011 issue of Story South.

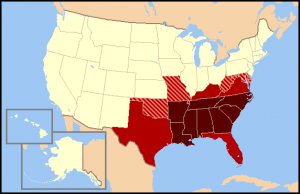

Anyone who’s spent any length of time living in the south knows that history is important to us. In the south, we cling to words like “tradition” and “heritage.” If you search the term “Deep South” on Wikipedia, you’ll find headings like History, Civil War, and Reconstruction. The recent debate concerning the Confederate battle flag only further demonstrated this, immediately prompting the construction of southern-based websites with titles like “Preserving the Southern Heritage” and “History not Hate.”

So why is this? Why, as southerners, are we so obsessed with the past? Is there something hidden in our redneck genes, something wriggling deep in our southern-fried DNA that causes us, as southerners, to cling to the past? One answer might be that as southerners we are so obsessed with the past that we simply aren’t interested or concerned with examining our present or our future. Some might even argue (mostly northerners I presume) that it’s precisely this kind of backward thinking, this constant looking to the past, that has led to the south’s obvious lack of progress, especially in terms of education, pollution, unemployment, and poverty. Regardless of your opinions one way or the other, it’s difficult to ignore the fact that these days young southern writers seem inexorably drawn to the south’s past, rather than its present. Over and over, young contemporary southern writers seem much more content to drudge knee-deep through the south’s bloody history than explore its present. And, when they aren’t exploring the south’s past, they seem much more compelled to rewrite great southern literary traditions than explore the south’s present, or even its future for that matter. Who can forget Susan Lori Parks’ wonderful tribute to Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying or Alice Randall’s rethinking of Mitchell’s Gone with The Wind. Don’t get me wrong. These are all wonderfully creative and skillful books, but as a southern writer in my thirties, I cannot help but wonder why such writers aren’t as equally concerned with examining the south’s present. More.

I think Tusa's essay (by the way, I read his book Dirty Little Angels and really liked it) hits me in some ways–the search for the new, however you find it, and in whatever time period–ought to be a primary goal of good regional writing, for instance. Not being from the South myself, I feel hesitant to say what I think of the thing in its entirety except to list books and writers I've read that argue against his view–Silas House's Clay's Quilt, the stories of Paula K. Gover, who no one seems to care about but me, Amy Greene's Bloodroot and so many more–doesn't really address the point. There are other names I could add and anthologies and books closer to home and among my friendslists I could suggest, but I see his point overall and don't want to distract, though my instinct is to kick against the idea. I do think Tusa could expand his reading, though.

I apologize if the rest of you saw this essay already, but I thought it worth mentioning here. I'm away from the computer for a few days and so won't approve comments until probably Saturday or so, but have at it if you like and I'll do the best I can to approve quickly.

.

Michael,

I didn't say anything about principles or values. My point is that contemporary southern literature doesn't accurately depict the contemporary south in terms of the people and their surroundings.

Southern literature isn't stuck in the past; it is literature about people who are stuck on principles and values worth being stuck on.

As far as Arkansas being southern, it looks like Brandon disagrees. When asked why he chose to set the novel he Arkansas, he said the following:

I like to write about places I've been to only briefly. If I know a place too well, and there's no mystery, I lose interest. If the place is too set in my mind, if I know every 7‑Eleven and car wash and know the people who work there, it's harder for me to mold that place into what I need it to be. Arkansas is a hard place to pin down, so anything seems possible. It's Southern, to be sure, but much of its history is Western. Oklahoma is right there, and that's prairie country. If you go north, into Missouri, you're in the Midwest. Most states, you know what you're getting into about five minutes after you arrive. To me, Arkansas isn't that way. Anything could be happening there. I guess I felt a lot of wiggle room, using Arkansas as a setting. Other writers would get that wiggle-room feeling from other places, I'm sure, like big, sexy cities.

On the McSweeney's site, a subscriber (Alex Vernon, of Little Rock, Arkansas) makes some interesting observations about Brandon's use of Arkansas as the setting (and title ) for his novel:

He says:

People outside Arkansas have trouble imaging where it sits on the map, and, I suspect, have less of a sense of the Natural State than they do of the state of my childhood, Kansas (flat wheatlands with open skies, Midwestern milquetoast Republicans, missile silos, tornadoes, and ruby slippers). Arkansas isn't the Deep South; it isn't the Midwest. It lacks the next-to-Texas quality of Oklahoma, even though it is next to Texas. As John Brandon's novel Arkansas quips, "Little Rock keeps embarrassing itself by trying to attract tourists, claiming to be a technological hub and cultural capital. Capital of what? The Northwestern Mid-South?" And elsewhere: "Here's your restaurant. The Heartland Fryer. Is this the heartland?"

Brandon's Arkansas isn't Arkansans' Arkansas. The novel does occasionally ground itself in recent state history, such as references to Little Rock's gang troubles of the early 1990s and the Mitch Mustain drama of the Razorbacks' 2006–2007 football season. But the novel also deliberately decouples itself from the state whose name it bears: the description of Hot Springs does not bother with accuracy, and the Barnett Building in downtown Little Rock does not exist. Actually, it does exist: it's the name of Brandon's parents' bank building in Florida.

Brandon has traveled through Arkansas a number of times, as he and his wife have crossed the country for her career. But he has never stayed in the state longer than a hotel night. In this sense, Brandon's Arkansas is Brandon's Arkansas. His transient experience informs the book. None of the major characters call Arkansas home; they each find themselves in the state accidentally. And though much of the novel is set in a park-ranger housing compound (including two trailer homes) at the Felsenthal wildlife refuge, in the southern part of the state, the characters' drifting nature and their constant drug- running turns the book into a road narrative.

The nowhereness of Arkansas to non-Arkansans, and the state's frontier heritage, pulls the imagination in a certain direction. Unlike Annie Proulx's Close Range: Wyoming Stories, this novel is bound by realism, but otherwise similarly locates itself in a place where—at least for its author—anything can happen. The Coen brothers' Fargo strikes me as a better comparison, in the use of a nowhere setting to explore acts of violence and character that just might actually occur. As with that movie's title, the book's title creates an interesting tension. Does the nowhere setting remove place as an influencing factor in order to highlight character, or is imagined nonplace itself a bit deterministic? "Arkansas is what I say it is," the book's drug boss declares. Really?

Hey Charles,

I never mentioned southern gothic fiction in my essay (or surrealistic fiction, or post-modern fiction, etc) because I agree that these traditions tend to distort setting and time. My problem is with contemporary fiction that postures itself as realism (set in the present-day south). All the writers you mentioned (Crews, Faulkner, Hannah, etc) wrote fiction that accurately depicted the current culture of their time. All I'm saying is that if you choose to write realism (set in contemporary south) have the courtesy to depict the south accurately.

I'm a bit late coming back to this fray. But, I would argue that Brandon's Arkansas is indeed a Southern novel. It's a lot of the New South that I think Tusa is interested in. It breaks with a lot of the stereotypes, and turns the usual caricatures on their heads. It makes use of the ways, as Tusa describes, new technologies have changed the face of the old South. And, while you may be right about the geography (as I have not spent much time in Arky myself, either), I think that's less of a concern. I think Brandon is precisely the "New Southern" writer, one simultaneously stuck in the past but also well-located in the present world of mobile devices and e‑criminals, identity theft, faux-intellectualism, etc.

In fact, some of the best aspects of Arkansas are its rather loud, embedded indictments of academic pretentiousness and naiveté.

Brandon's novel ARKANSAS is not a southern novel. He just uses Arkansas as a setting — fails to even understand the basic geography of the place. I don't think he's ever been there, in fact. Just FYI.

Hey Jason,

Are you reading at the Fairhope conference this weekend by chance? I saw your name on the reading schedule, and I figured it might be you (even though Stuart is a fairly common name).

Chris

Chris,

I've got to take serious issue with this claim, mainly because I feel like you grossly oversimplify. Gothic and realistic traditions work in fundamentally different ways. In creating a Gothic dream, even one set in the present, one cannot delve too far into minute "realistic" details without doing violence to the illusion that is at the heart of this kind of storytelling. You seem to be making a rather broad polemic, one that ignores this important aesthetic truth. And it does so happen that many Southern writers do work in this tradition, going all the way back to Poe, thence to Faulkner, McCullers, O'Connor, Crews, Hannah, etc.

Also, Ron Rash has written at least two novels and several short stories set in the present. Chris Holbrook's story collections, Crystal Wilkinson's, Chris Offutt's, most of Alex Taylor's collection NAME OF THE NEAREST RIVER, John McManus, the list goes on and on.

Daniel Woodrell is a master. Not a big fan of Silas House. He seems to be writing about a place that doesn't exist. Love Franklin's short stories, especially The Nap (an incredible story if you haven't read it). Hadn't heard of Brandon, but I checked him out, and his novel, Arkansas, seems right up my alley. Thanks for the suggestion.

Hey Guys,

My point (and perhaps I didn't convey it as clear as I would have liked) was that southern literature doesn't seem very contemporary. Believe me, Jason, middle class, suburban, white-collar stories are not what I want. I love stories with Meth labs and pickup trucks. I simply think they should be written about in a more contemporary context (throw a GPS system in the pickup. Put the Meth lab in an abandoned Burger King). Most of the southern books I read these days seem as if they are trying to be southern. The books are populated by characters who seem detached from technology (and from the American culture as a whole), which to me is simply not believable. The south is presented as some impoverished, racist place (which in some ways it is), but what’s interesting to me is that many writers seem to purposefully avoid any reference to civilization or technology. It’s as if the writer thinks that the story will be less authentic, less southern, if he/she mentions Walmart or Blockbuster or Youtube. I guess I’m just suspicious of books that act as if technology hasn’t altered the landscape of the impoverished south, especially when I know it has. By the way, Woodrell happens to be one of my favorite writers (Sweet Mister could easily be my favorite book of all time).

Stuck in the past or excluded from the future seems to be the question.

Convergence models in nature and rural culture, which can inform contemporary art, creative economy and sustainability practices, remain virtually unknown or ignored by various "innovators" in those fields.

Say CSA with regard to the South and most people make the obvious association. Say CSA absent any "southern" connotation here in the Northeast and most people think community supported agriculture.

We southerners often find ourselves stuck in a past, safely out of the future, in field like community farming practices where experience matters.

I have worked on projects with organic farms in the Northeast, including bought and split shares in CSAs here, and I can say for sure that the way my grandma and her neighbors leveraged their individual veggie yield engendered community in a more organic, efficient and a less commercially-administered way than CSAs.

Too many CSAs find recent immigrants bringing precious agriculture skills to bear through hard work on plots of land, with low pay, for distribution primarily to shareholders who can afford the premium for CSA produce.

I can say for definite certain that my grandma and her neighbors' practice of growing what interested them, almost always including some items their neighbors did not grow, then trading their produce with each other, engendered true community in a way that CSAs do not.

But this is not to say Long Live the CSA. My own family history is too complicated for that simple view. But I do take pride when I see how my old granny and her neighbors did something CSA-like in a way that most sustainability gurus can't see through the forest of their trees.

She is the past. They are the future. Like that.

Since I can't post comments on the original post, I will mention them here. I think some of what Tusa wants is a bit of middle class wishful thinking. I got a lot, and I mean a LOT, of this same rhetoric in the workshops at South Mississippi. "Write what you know. Not this meth-head, pickup driving stuff. Write what you know!" they yelled and yelled at me. Sad news, then and now, friends, THAT is what I know.

Could Southern Literature use a good kick in the pants? Maybe so. But, Daniel Woodrell is doing fine work up there in the Ozarks, stereotypes or no. Tom Franklin's new Crooked Letter is a good entry, as are both of John Brandon's offerings thus far.

But, the simple truth is, meth-heads and pickups remain what a great many of us (those of us with calluses on our hands) know. Do I wish I knew other things? Sure. I wish I knew nice, fat lives growing up in the suburbs with a two-car garage and a whitecoller dad. But, then I probably wouldn't be a writer.