Bras covered the back of the car. They draped over the seats and wrapped over the seat belts and hung from the door handles and carpeted the floor, as if a band of horny teenagers had taken the Buick for an orgy joy ride. But these were not the bras of teenagers. They were thick-strapped and sturdy and made of plain white cotton, the kinds of bras bought in packs and tossed into a grocery cart.

With these bras, George knew there were also french fries and cheerios and smears of jam and peanut butter. Some nights his dreams filled with roaches gnawing at the stains, and then the seats, and then working their way toward him until he sat on the road, the Buick gone save the steering wheel in his hands. Within the dream this filled him with panic, but when he awoke, he would close his eyes and pretend to continue the dream, so that an eighteen wheeler screeched its jake brake, but could not stop in time.

In all other ways the car was immaculate. George kept the front vacuumed and dusted. He changed the oil, and rotated the tires, and made his mechanic perform a tune-up every five thousand miles, though the mechanic assured him this was not necessary and usually did no more than blow-out a filter and bill him for the full labor. This was how George lived, and there was no one in his life to demand he do otherwise.

Just as there was no one to tell him this trip was a bad idea, to warn him that truth rarely brings understanding. He’d taken a week off from his job as an Assistant Principal at Lake Dallas Middle School, and was now driving narrow, unmarked highways through Eastern Oklahoma with a map resting on the passenger seat and an I‑Pod twice through an Eagles playlist.

George slowed as he passed a mileage sign. He checked the nearest name against the piece of paper crinkled and damp in his hand. PANOLA. PA-no-LA? pa-NO-la? PAN-ola? His wife had never spoken the name, not once in their life together. It was always just ‘back home,’ or ‘where I’m from.’ And even that was a rare occasion.

A speed limit warning arrived, then a sign welcoming him to town and listing the state championship years of various high school sports. A few houses appeared, squat and siding plated. Plastic flower containers hung from front porch hooks. Televisions flickered behind mini blinds. George rolled past darkened storefronts—a pharmacy, a diner, a dollar general. He could not tell if these places were closed for the night or for forever.

At the edge of anything that could be called town, George paused at a flashing yellow stoplight and circled back. No hotel. No sign for one since McAlister. Maybe there was one farther east. The gas station was open. George would use the restroom, ask the clerk for advice.

A handful of flat bed diesel trucks sat rumbling near the entrance. Inside, George nodded at the group of men gathered around the cash register. Each wore jeans and work boots and long-sleeved shirts. Two had goatees. One had a giant, unruly beard. Hard men. Masculine men. The kind of man his father had been. The men quieted as George made his way to the toilet. He could feel their eyes on him and his skin grew hot, the way it did in faculty meetings when the Principal made a joke at his expense.

George needed to go, but would not be able to do so with those men hulking outside. He flushed so they would not guess his problem, then splashed his face and dried it with a paper towel. He used the mirror to adjust his posture. This was something Lauren had taught him. The appearance of confidence, of belonging, could get a person through.

In the store, George grabbed a Dr. Pepper and a Hershey Bar. He placed the items onto the counter, asked if the cashier could point him toward the nearest hotel. The cashier lifted a pen from a coffee mug and poked at the candy bar as if it were maggot-ridden.

“A hotel, huh?” the cashier asked.

Lauren had sounded like this man when she was angry, or after too many glasses of wine. She had maybe known this man, had entire twangy conversations with him.

“Been driving all day,” George said. “Could use twenty winks.” He cringed at his own attempt at folksiness. At least the men from before had left. At least there was just this one man to witness his embarrassment.

The cashier tapped the pen against the Hershey Bar. “Sweet tooth?” he asked.

George patted his stomach and laughed a little. “Unfortunately,” he said, but he could tell the cashier did not buy his attempt at casual self-deference. George opened his wallet to pay, hoped this might speed the exchange along.

“I bet you do,” said the man, and he plucked the wallet and raised it into the air. “I just bet George here likes ‘em real sweet,” he said, and George turned to find the men from earlier gathered into a tight semi-circle behind him. George lifted his hands.

“Take whatever you want,” he said. “I’ll leave right now. I won’t even call the cops.”

One of the men stepped forward and crowded George until his back was pressed against the counter.

“That what you do?” he asked. “Take whatever you want?” He turned back to his friends, gestured to George with a half-circle of his arm. “I think our friend here thinks he can take whatever he wants,” he said, then he grabbed George’s shoulders and twisted him to the ground and stomped a work boot onto George’s chest.

“Where is she?” he asked. George grasped at the man’s boot, but could not budge it. His legs flailed on the tile floor. “WHERE IS SHE?” the man repeated and stood harder on George’s chest.

“Can’t do this here,” someone said.

“Fine,” said the man standing on George. “Let’s go.” Then George knew only the swirled rubber tread of the man’s work boot before it smashed into his skull.

George thought that he was blind, that the blow from the man’s boot had severed his ocular nerves. This happened to a Cowboy’s running back, and he’d put together a lesson for his Biology class, had hoped to steer a few minds away from the sport of football with its head injuries and manic depressions and hair-trigger rage. Back when he was a teacher and thought he always would be. Before he ever had designs on an administrative paycheck. Before he met Lauren.

As his eyes adjusted, George realized the dark was night, and he wondered if it was the same night or another one, since he had no idea how long he’d been unconscious. His fingertips tingled. He tried to move and found his wrists zip-tied, his ankles the same. The plastic cut into his flesh. He tried to stand, but could only bring himself to his knees.

“Hello?” he asked. He said the word a few more times, then changed the word to ‘help,’ which he yelled as best he could through his throbbing head until he realized that if they had not gagged him, there was no one to hear.

And no one to look for him. Not until next week. And even then, the School Board would be contacted before the police.

George called out again, though this time he did so to gauge the size of the room, the materials around him. It seemed he was in a house, though there was also a dank, rotting smell that reminded him of being in the woods with his father, one of the dozen times George had let a buck sniff through a clearing unharmed. There was something acrid in the air as well, strong enough to burn his nose through the clotted blood.

George fiddled with the zip ties, but knew it was pointless. About once a year an older male student would steal the custodian’s zip ties and lash a younger male student to the bleachers, or the flag pole, or the girls’ locker room door. It would take a sharp knife to free him.

Maybe there was something nearby. Some piece of broken metal or glass. George lowered his elbows to the floor, began a slow, awkward crawl in search of anything that might cut through the thick plastic.

When light began to rise, his knees and elbows were bloody, though he had not travelled far. He had been right about the place. It was a house, or had been one sometime before. Cabinets were warped and split. Parts of the floor were sunken. Piles of rat shit stood inches deep near old couches. A place no one came to or went from. The kind of place a body might rot away in for years before a golden retriever laid a femur on the porch steps of a nearby home.

A truck engine approached. George tried to compose himself. He attended seminars every year on conflict management and group aggression, spent weeks afterward reading studies and looking at videos on the internet.

“The only people interested in studying violence are the ones who’ve never lived it,” Lauren would say when he would try to discuss some fascinating new theory or experiment, then she would take her glass of wine and her Ambien and leave him to it.

Disinhibition. This was the biggest hurdle. These men had lost their individuality, their self-awareness, their self-evaluation apprehension. But there was always one group member who had not yet succumbed. There was always a Doubter.

Of course, The Doubter would be difficult to spot. Once a dynamic formed, the speech and appearance, even the physical gestures of the group members mirrored each other. George would need to observe their actions closely, employ the process of elimination.

The easiest person to name would be the Leader. They were the first to act, to speak, and the others followed in kind. They led because they held an unwavering belief in the group’s actions. George had always understood the possibility of failure. This is why he would always be the Assistant Principal. And why part of him understood what Lauren had done. Was he angry? The anger he felt would not cease or simmer. But did he understand? Yes. Some part of it, at least, he understood.

Truck doors shut and boots clomped toward him. George sat-up as straight as possible and faced the men as they entered. The men walked toward George in unison and formed the familiar semi-circle around him. One held a bra. One held his phone. One held a short piece of rebar. They began to speak.

“How many, George?”

“How long?”

“Fucking sicko.”

“Fucking perve.”

“Five phone numbers? Not even a Mom or Dad?”

George did not speak. What could he have said? ‘I stopped calling the friends who stopped answering. I stopped answering the ones who called. My father died years ago. My mother of grief. Dementia, they said. Genetic. Nothing to do with football.

The men waited in silence for a few moments, then Rebar Man lifted his weapon. George closed his eyes.

When the blow did not come, George saw that Bra Man held Rebar Man’s arm. There was a small struggle, but Rebar Man lowered the weapon. Bra Man patted Rebar Man’s shoulder, then moved past him to squat in front of George. This man. This man was The Doubter. George made eye-contact, did his best to be as human as possible.

“Look,” said The Doubter. “We just want to know if she’s okay. Can you tell us that? Can you tell us if she’s okay?”

George knew the man did not speak of Lauren or Annabelle, but his words were the same as those of the police officers who had yelled coffee breath into his face while waving photographs of his wife and daughter. One photo in particular. Christmas. Lauren in a soft, gold dress. Her hair sleek and loose around her shoulders. Annabelle in dark green velvet. A gold bow around her chubby waist. They smiled. At the camera. At him through the camera. George moaned.

It was an animal sound. It was a mistake.

“What’s that?” asked The Doubter. He leaned toward George.

George cleared his head of Christmas and smiles. He took a breath. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said. He made his voice steady. I am a human, this voice insisted. I use language. I’m a man. A man just like you.

The men behind The Doubter grumbled and shuffled. The Doubter glanced over his shoulder, then turned back to George and placed his hands on George’s shoulders the way George had seen fathers embrace their sons on the first day of a new school.

“Look, George. We just want our girl back. We just want Christine. Just tell us where Christine is and we’ll give you a three day start outta here. Three days and you could be in Mexico.”

George wondered if Christine was his daughter, or Rebar’s daughter, or if she belonged to one of the men who had not spoken. Was she a little girl? A teenager? A toddler? George opened his mouth. The Doubter leaned closer.

“I. Don’t know. What. You’re talking about,” he said. He thought the repetition of these words would make them strong, would let The Doubter hear their integrity, but The Doubter’s eyes darkened and he stepped back and nodded at Rebar Man. George knew too late that Bra Man was the Leader. Rebar, with his impulse to rage, could never lead a group of men. Rebar swung his arm. George did not pass-out this time, though he wished many times that he could.

When the men finished, they left the room. As the pain loosened its hold on his brain, George assembled the story thus far.

There was a girl, Christine, and she was missing, and these men were looking for her, had been looking for her last night, had gathered at the gas station to form a plan when in walked a stranger, a stranger with bras covering the backseat of his car.

The men were just outside the door. George could hear their voices and the occasional cough and spit. A phone rang. Someone spoke. George could not hear the exchange, but there was nothing in the man’s voice to suggest that anything had changed. The girl was still missing. George was still to blame.

He considered going along with it, pretending to be the one who could show them Christine. This would buy him time, would get him out of the house. But what then? And what if she was found beaten? Or dead?

He could try to escape. But even if he managed to free his hands and feet, he would not survive more than a day on his own. These were men who could track a wounded animal.

He could not bluff and he could not run, which meant he would have to reason. He had chosen the wrong man, made the wrong man The Doubter. But one of them deserved this title. One would listen long enough to stay the hands of his friends. George propped himself against the rough pine wall. He would begin with why he had come here. This would link them, make him part of their group, define him as an insider.

‘Lauren and Annabelle Sloan,’ he would say. There would be a pause, and George would say the names again. ‘Lauren and Annabelle Sloan. My wife. My daughter.’

This should be enough. The story had made national news. Lauren’s name was now a congressional bill. And once George could see that the men recognized these names, he would tell them that the woman on TV was one of their own, a holler girl who moved to the city and carved her nose and flattened her accent and snared herself a man she thought was on his way up in the world because he was the son of a famous football player and she thought that meant material comfort enough to cushion the violations of her first nineteen years.

‘You must have known her,’ he would say. ‘A town like this. A father like that.’

Maybe if he began his story at that point, maybe this would help them see that he was not the evil stranger they thought him to be, or at least convince them he deserved a chance to explain.

And George would explain, if they would let him. He would explain that the only way to get his daughter into the car for daycare was to let her fondle a bra on the drive, that the doctors said she had done this while nursing, that it was an attachment thing, and that she would grow out of it, and that there was no harm in indulging her for a little while. They had used Lauren’s bras in the beginning, but it got to the point that they bought the cheapest ones they could find, and all those bras just accumulated back there, because they didn’t have any other purpose, and eventually, no one even noticed them. To their family, this was where the bras belonged.

And then George would tell them what he had not told anyone, because there was no one to tell. He would tell them that he had thrown away make-up and hair gel and soaps and shampoos and baby food. Had donated coats and shoes and most of the furniture. Had packed away photo albums and books. But every time he took a trash bag to the car and lifted one of those bras from the backseat, he wound-up on his knees in the driveway.

‘I stopped trying after awhile,’ George would say. ‘After awhile, a person stops trying.’

There would be silence, then Rebar Man would pull a large knife from his belt and slice through the zip ties on George’s wrists. The men would apologize. George would tell them that there were no hard feelings.

‘Were my own daughter alive,’ he would say, ‘I’d want men just like you looking out for her.’

“Lauren Sloan,” George said aloud through his busted lips and swollen jaw. “Annabelle Sloan. My wife. My daughter.” Yes, thought George. These would be the words that would free him.

But the men did not enter the room. A woman appeared. A woman wearing a sweater over a long cotton dress. Her hair was loose and a breeze blew it wild around her head as she paused in the doorway. George smelled something sweet as she approached. Not strong enough to be perfume. Soap maybe. Or detergent. It seemed she could not belong to the men who had put him here.

The woman knelt before him. George winced when she lifted her hands and the woman made a shushing noise before laying her palms against his broken face.

“George? It’s George, isn’t it?” she asked.

George nodded. The woman began to stroke George’s brow and cheeks; she made tsking noises over his injuries.

“It’s okay,” she said. “It’s going to be okay. Just help me, George. Please. Please help me.”

George had said these same words to his neighbors, to the cops. This woman. Christine was this woman’s girl. George knew the scratched-out, jangly nerves, the sense that nothing in the world was solid, of falling and never touching bottom. They were alike, she and him. There was no one who understood this woman better in that moment than he did.

Which is how George knew she would listen. She might make him repeat the story several times, might look for cracks in the cause and effect, but she would listen, and she would know it was the truth. There was no way to shake his story apart. George had tried. God, how he had tried.

And so George told the woman about Lauren and Annabelle and what had happened and why he had come here. When he finished, there were tears in her eyes and she stroked his hair.

“No wonder,” said the woman. “It’s no wonder at all.” George began to cry then, and the woman sang nonsense words in her rough, low voice. When George quieted, the woman lifted his face.

“Better now?” she asked.

George nodded.

“Good,” she said and placed her thumbs on either side of his broken nose. “You understand, George. Your Annabelle. My Christine. It’s a hard thing, but it’s true. When it comes to your child, you’ll do anything, sacrifice whoever.” George nodded. Had it meant saving his daughter, he would have placed every kid at Lake Dallas Middle School on a bus and set them on the bottom of that lake.

“So, George? George, I am truly sorry about Lauren and Annabelle. And I understand, trust me I understand how something like this can boil-up a part of yourself you thought gone forever, a part you thought Jesus had washed away years ago.” She pressed her thumbs hard against the fractured bones of George’s face. George gasped.

“Where’s my Christine?” she asked.

“Lauren Sloan,” George stammered. “Annabelle Sloan.” But the pressure on his nose did not relent.

“Christine, George. I need you to tell me about Christine.” George writhed, but could not break her grip.

“Lauren Sloan,” George said louder. “Annabelle Sloan.” The woman pressed harder.

“Come on, George,” she said. “Come on, now.”

And then somehow, without thinking the words, George said, “I’m sorry.”

The woman lifted her thumbs and asked him to repeat what he had said.

George fell to his side panting. Again, he tried to speak their names, but again the words that emerged were, “I’m sorry.”

The woman stood. George tried to call-out to her, but could only repeat ‘I’m sorry’ over and over again.

The woman backed away from him. George reached for her, wanted to ball her hair into his fists, jam it into his mouth, dam those words.

George watched the woman lift the rebar near the door. Her eyes. He knew the panic there, the disbelief, the rage.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

The woman gave a wild, terrified scream and began to beat him. George drew his arms as best he could over his head. A blow snapped his rib. The rib pierced his lung. Had George found the words to save him—the note Lauren left, his father’s name, the color of a two year old child ten hours submerged in lake water—had George found these words, he would not have had the air to speak them.

Amanda Bales received her MFA from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Her work has appeared in The Nashville Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Southern Humanities Review, and elsewhere. She lives in central Missouri.

Amanda Bales received her MFA from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Her work has appeared in The Nashville Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Southern Humanities Review, and elsewhere. She lives in central Missouri.

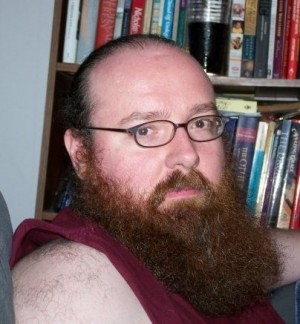

This is always a tricky question, as I’m involved in several different projects at a time. Right now I’m nearly ready to shop a manuscript of poems called Dear So and So, in which I address poems anonymously to a number of people who may or may not be in a position to answer, or willing to talk with me at all, considering our various histories. It’s a series of off-sonnets and other near poems, like in-jokes from my life, which others might have fun reading. I’m also researching a short book on the video game Redneck Rampage, which game nearly consumed my soul in the 1990s just as I was ordering my life and goals and writing in light of the fact that I was Appalachian, 41.7% more likely to die of a heart attack than my peers, and destined to have a love/hate relationship with the area in which I grew up. Beyond that, I have another nameless manuscript of poems which should straighten up and behave itself soon or I’m going to whip its ass, and a novel called The Arsonist, again set in my hometown and surrounds, in which a state social worker, Kathleen Brake, gets increasingly drawn into the psychoses of a crazy but charismatic teenage arsonist named Johnny Jones while negotiating the terrors of adolescent relationships with her fifteen-year-old daughter Angie and her own love life with her well-meaning but feckless husband Gallow. And her short-term lover Brady Bragg. All have secrets, all have needs, and when the flames rise, everyone will be affected.

This is always a tricky question, as I’m involved in several different projects at a time. Right now I’m nearly ready to shop a manuscript of poems called Dear So and So, in which I address poems anonymously to a number of people who may or may not be in a position to answer, or willing to talk with me at all, considering our various histories. It’s a series of off-sonnets and other near poems, like in-jokes from my life, which others might have fun reading. I’m also researching a short book on the video game Redneck Rampage, which game nearly consumed my soul in the 1990s just as I was ordering my life and goals and writing in light of the fact that I was Appalachian, 41.7% more likely to die of a heart attack than my peers, and destined to have a love/hate relationship with the area in which I grew up. Beyond that, I have another nameless manuscript of poems which should straighten up and behave itself soon or I’m going to whip its ass, and a novel called The Arsonist, again set in my hometown and surrounds, in which a state social worker, Kathleen Brake, gets increasingly drawn into the psychoses of a crazy but charismatic teenage arsonist named Johnny Jones while negotiating the terrors of adolescent relationships with her fifteen-year-old daughter Angie and her own love life with her well-meaning but feckless husband Gallow. And her short-term lover Brady Bragg. All have secrets, all have needs, and when the flames rise, everyone will be affected. I write in a mode many others do, but I believe my work stands out because of its focus on rural matters, nearly exclusively, and because I try to use as few words as possible to make the story I want to make up. I also believe my stories are emotionally true where others often seem fake. Probably the fakers feel the same way about me and my work. The difference is that I’m right where they’re wrong. 🙂

I write in a mode many others do, but I believe my work stands out because of its focus on rural matters, nearly exclusively, and because I try to use as few words as possible to make the story I want to make up. I also believe my stories are emotionally true where others often seem fake. Probably the fakers feel the same way about me and my work. The difference is that I’m right where they’re wrong. 🙂 I have little else to do outside obligations to my immediate family. I have no important skills I can rely on, no rich family to support me in my efforts to produce art, no great intellect to make it easier on me, but I do have a history 250 years deep in a small area of Pennsylvania that so far has yielded material enough for at least three writing careers, and I trust, will continue to provide such long after I’m gone.

I have little else to do outside obligations to my immediate family. I have no important skills I can rely on, no rich family to support me in my efforts to produce art, no great intellect to make it easier on me, but I do have a history 250 years deep in a small area of Pennsylvania that so far has yielded material enough for at least three writing careers, and I trust, will continue to provide such long after I’m gone.