Dad is thinking about me and a woman, but he has forgotten he is doing it. The heater in the truck makes the windows sweat on the inside and drip in lines like crying, and the lights of the cars and blinking signs and traffic signals get smeared in the water, so it is hard to see through. Dad / trembling inside but suppress that and don't be exited. this is not me tonight. it is for Kyle, a man, this kindness or desperation / yanks the sleeve of his coat down over his fist and rubs a hole in the smeared light and bends toward it and looks. Then he parks and we get out of the truck, and the cold air burns in our chests and our mouths smoke. Dad's boot slides on old ice that the rain has pocked and rotted, and he halfway falls but catches the side of the truckbed with a thump and says, “Fuck,” the word snapping like a jerked string in the empty, dark parking lot. Dad is not my father. My father had horns as wide as stretched arms and fist-big balls that swung down to his knees, and his breath blew from his wide nostrils so hard and hot that it singed the hairs on the back of my soft mother's neck. Dad killed my father just after I was born. He braced himself wide-legged, lock-kneed and close and shot him between the eyes, and Father's blood streamed out like a rope that tied him to the ground until he could never move again. I saw that in a dream.

I am thinking about Calf. It is earlier, in the barn with the wind knocking on the tin above us, and I am petting the soft hair on the slope of Calf's neck and scratching between his ears. Calf sucked hard and wet on my finger and his tongue rough, as if he thought my hand was his mother. He pushed with his nose and searched for milk.

We go inside and force the door closed against the dark, and I follow Dad to a table beside the wall.

“This is a good table,” Dad says.

“Kay,” I say. We sit. My chair has one short leg, so that it rocks from side to side. I shift the weight on my hips to make it rock and the short leg clicks on the floor.

“Sit still, Kyle,” Dad says.

“Kay.” I stop rocking.

Dad says, “I like to sit in a corner, where you can keep an eye on things. Never sit with your back to the door. That's how they got Wild Bill Hickok.” He points a finger at me like a gun and winks to aim and lowers his thumb to shoot me between the eyes. It feels like a little hole opens.

“Kay.”

I hug myself and shiver. “It's cold.”

“On a night like this, my dad used to say it's colder than a well-digger's ass. I don't know where he got that, but it makes sense, if you think about it. I guess I'm going to have to get that heater fixed in the truck. You'll warm up in here, though, just take a few minutes. You spent too long out in that barn today. I don't wonder you're cold.”

The waitress comes to us. She wears ordinary clothes, not a uniform, though she has a flower-strewn apron and a pad for writing. She has an extra pen stuck in her hair. She smiles.

“Get you guys anything?” she asks.

“I'll have a beer,” Dad says.

“What kind? We got just about anything you want.”

“Um, Budweiser.”

“What about you, honey?”

Dad / it is not for me — though for me too isn't it? for this jealousy embraced like a big soft bag of spilling dirt against my chest my body coaxed and pummeled to desperate failure alone in the darkness of the bed while his young and ignorant staining the bedsheets with semen over and over as if to the softest touch of any breeze / says to me, “Tell her what you want.” To the waitress he says, “He's a little shy. More than a little.”

The words are in my throat. I taste them sweet and fizzing like the thing before I can say and push them stumbling out with my tongue. “Root beer.”

“There you go. One Bud and one root beer, coming up.”

The waitress leaves.

“Is Calf okay? He might be cold,” I ask Dad. Calf shivered for a long time when he was born. He was wet and his mama licked him all over, as if her broad pink tongue was sculpting his flesh into shape for this world and warming him, which is love.

“He's fine, I reckon.”

“He was shivering when he tried to stand up. It's cold tonight. Calf is little.”

“Don't worry, his mom will keep him warm. I'll bet he's laying up against her in the barn right now, with his belly tight on warm milk, snugger than either one of us.”

I think about how happy Calf is. It makes me feel so good that I hurt.

The waitress comes back. She puts two napkins on the table, then sets down the bottle of beer and the glass of root beer.

“What else can I get for you?” she asks. “The shrimp basket is the special tonight.”

“You want a hot dog or something?” Dad asks.

I shake my head. She leaves.

Dad takes a drink.

“Aren't you going to drink your pop?” Dad asks.

“I hope Calf ain't cold. He is pretty.”

“The prettiest I've ever seen.” Dad / damned scrawny / stands up. “I'm going to go to the rest room, then I'm going to talk to somebody over there. You stay here.”

“Kay.”

Dad leaves. I sit still for a while and look at the table, then I look at the black window where the lights in the ceiling behind me are shining. I take the car out of my pocket and push it slowly to the edge of the table, then catch it after it falls. I think about Calf. The wind never stopped for a second today, as if all the great and winter-scoured plains to the west had tipped like a plate to pour their icy spirits out over the little farms. The wind blundered and stumbled through the bony trees, but swift in the open fields its lithe, silken fingers rubbed the air into flakes that scattered randomly and without accumulation above the freeze-clotted veins of earth. I wonder if my mother is cold in the earth. The wispiest, softest frizz of hair frames her face and catches whatever light is available from sun or lamp into its brown, blonde edges, so that she always shines. Calf's mother pissed before he was born, hot-smelling a wrist-thick gush of cowpiss shining from her into the barn straw, why? To make room for his passage from her body. Did my mother have to void herself to ease my coming through her? Calf fell from her swathed in her thick bloody wet that she licked away until he could stand, shaking almost too much to push himself up, spindle-legged, weak and as if astonished to breathe. He thought my fingers were teats in his still unteethed hard pink mouth, sucking to pull more life down his throat, needing the pliable pale thread of milk that he will braid into bone and flesh. We left the light on in the barn. Dad was silent, coming here, except sometimes huffing a cough into his sleeve, and both our smells are different because of the aftershave we abraded burning into our razor-freshened skin side-by-side at the mirror. This is somehow the flesh, too, rising trembling in trepidation and poverty, hanging racked on its scaffold of wet bone to ask for more life, bawling beyond volition into time at once as and not as Calf bawls hunger into the edge of the wind. I didn't know I was crying until I left the barn and the cold groped for and found the wet on my face. Dad said nothing about my unmanly tears.

“This is Kyle,” Dad / not for me, how many years since that for me, old man pummeling his own flesh uselessly in the dark bedroom? / says. He sits in his chair again, and a woman sits in another chair.

The woman says, “Hey, fella. Your son?”

“Stepson. Say hello, Kyle. This is Tina. He's shy. Say hello.”

“Hi,” I say.

“How's it going?” Tina asks. She has little lines beside her eyes, like her hair is pulled back too tight. Her eyes are not like Mom's. She drinks from a glass with ice clicking in it. She has a cigarette between fingers yellowed from many other cigarettes. She pulls smoke into her mouth and waits a few seconds and breathes it out.

“Good, I guess.” I nudge the car toward the edge of the table.

“He's a little slow, huh? But that's okay.”

Dad says, “He's a good boy.”

“Sure. I know he is. How old are you, Kyle?”

I say, “Seventeen.”

Dad says, “Nineteen. You're nineteen now, Kyle. Remember? Two birthdays since Mom left. He can't handle numbers, but he is pretty good with everything else. He understands a lot more than he can put into words, don't doubt that, a lot more than you think.” When he says left he means died.

“What are you boys up to tonight?”

“Just having a look around. Bored with sitting at home, I guess.”

“Where's that, home?”

“Up near Wabash.”

“That's not so far, I been to Wabash lots of times, but I haven't seen you around before.”

“No.”

There is a silence.

“Well, do you want a party, Willis?”

“Let's just talk a little first.”

She shrugs and smokes.

“Not much happening in this place tonight, that's for sure. ”

Another silence.

“Do you think Calf is cold?” I ask Dad. He looks / embarrassed, the damned calf again / mad when I ask.

“Cath? Is that your girlfriend, Kyle?” Tina says.

I blush warm like blood seeping through my face. “No, no!”

“He said 'Calf,'” Dad says, “like a baby cow. One of our cows had a calf this morning, and Kyle named it Calf. Not very imaginative. He loves it. He hasn't talked about anything else all day long.”

“Oh, that's fine,” Tina says. “When we were kids, my brother had a dog named Dog. He was a mean fucker, I mean the dog, except when he was with Frankie. Followed my brother around everywhere he went and never bit anybody, then.”

“I think everybody used to have a dog named Dog,” Dad / my body is a dog named Dog / says.

“Is Calf okay?”

“He's fine, Kyle.”

“What if the dogs come?” Tina talking made me think about the dogs.

“They won't tonight. That's enough questions for a while. Let's talk to Tina.” Dad's voice is tired. Everybody is quiet. The wind pushes on the window.

“Well, then,” Tina says. “What's it's going to be? Do you want a party?”

“How much?” Dad asks.

“What you want to do?”

“Just ordinary, I guess.”

“You mean straight sex. A hundred and fifty.”

Dad looks at the window, as if he is trying to find the dark.

“A hundred.”

“One twenty-five, and only because it's a Tuesday and too damn cold for reasonable people to be out. We can use a room upstairs, so you don't have to pay for a room. Pay me when we get up there.”

Something hurts Dad. He looks like a fist is clenching and opening and clenching again in his mouth.

“Not me,” he says. “I'm not going.”

Tina's mouth is open. A curly thread of cigarette smoke leaves it. She looks at Dad and looks at me and looks at Dad. I push the car off the edge of the table and catch it. The car is red.

“Oh, Jesus fuck. No,” Tina says. She stands and leans on her hand on the table, pushing down, the backs of her fingers white because the blood is pushed out. “Fucking hell no.”

“Wait,” Dad says. His voice is a wire in his mouth.

Tina picks up her glass and the ice clicks against the sides. She leaves.

The dogs. In summer the corn is high and the sussurant wind breathes through the fields with a noise like the beginning of sleep, higher and lower all day long according to the wind, the ribbed green blades rubbing together, the dense hot green shadow under the mat of leaves risen from earth like a fluid around the stalks. “Wait,” Dad says again as she is walking away. The dogs came through, breaking the stalks, rolling over them as if fighting. One dog had the fawn's throat between its teeth, and the other bit the thin bone of a hind leg, just above the foot, thrashing their heads back and forth, the fawn a limp rag between them as they wrestled and rolled on the ground and stood and pulled. The doe reared on her hind legs around them, squealing thin and hopeless panic, a mother's sound blue and bright like the edge of the flame from an acetylene torch, her front hooves digging circles in the air, trying to find a grip and climb away, until the dogs bore the dead fawn back into the corn, still fighting over it, and the doe stood still, her head lowered between exhausted splayed legs. Did I close the door of the barn before we left? Soft small things are easy to hurt. When I think that the dogs might come back and find Calf, it hurts so bad that I am afraid I might wet my pants.

Tina comes and stands beside the table.

“What am I supposed to do?” Dad, staring angry at the table / come stiffened on his bedsheets every morning and the whole question rising up in him between his thighs between his shoulders in his eyes like a warm animal heaving slowly its back up through the brown dirt and shaking and looking around for what this means or maybe even poisoned with longing the longing a poison because he doesn't know longing for what, and what can I do? / asks. “Does he have to live his whole life without anything?”

“Just me and him go up. You stay here.”

Dad's face looks sick, or like he has bitten something so sour it makes his teeth ache.

“Fuck yes, I stay here,” he says. “What do you think I want? What do you think this is?”

Tina says, “Two hundred.”

Dad does not argue. He takes money from his wallet and gives it to Tina.

“What am I supposed to do?” Dad / not for me nothing for me only numb inert nothing for me / says again. “Every morning his sheet is wet with come, but I don't think he even knows he's a man or what to do for himself. Maybe you could at least show him that.”

“I don't know what you're supposed to do, but I know what I'm supposed to do. I'm supposed to make a fucking car payment in the morning, and nobody but me to get it done. Doesn't matter to me, if you can't get it up and have to send him to do it all for you.” She sounds mean, angry, too. She puts the money in her pocket. She takes my hand and pulls. “Come on,” she says. “Kay,” I say. I reach for the red car but miss it as she pulls me, and it falls.

We go out. When Tina opens the door, the cold pours in like a bucket of thrown water, and I think we are going out into a place where everything will shine with a layer of frost, the windows, the parked cars, the clumps of weed and grass and leafless bushes stripped and trembling like wired toy armatures of bone in the waste beyond the parking lot, all varnished and shining with clean ice, as it is on some mornings that I like, but nothing is frozen yet, only raw wet still from the rain before, and the wind working rough and raw on any skin it can find. The moon inside the clouds is a white liquid bruise. Our shoes when we go out are like breaking sticks on the concrete, then we are on hard slick dirt, and Tina leads me around the corner into at first the blind dark, then what light there is settles into my eyes, and there is a metal stair on the side of the building. As we go up, the stair creaks and shakes, and thin drops of freezing rainwater shake from the steps and splash on the ground underneath.

In the room Tina turns on a light, and the shadows jump away from us. Tina shivers. She turns a dial beside the door, and warm air purrs from vents along the walls, and I think I can see heat shimmering above the vents like a road in summer. She says, “You can go ahead and get undressed. I'll be right back.” She goes into the bathroom without turning a light on in there. She leaves the door half-open, and I hear her peeing and think of Calf, happy and fine tonight, sleeping against his mother. There is not much in the room, a few metal chairs folded against one wall and a long, narrow couch covered in green cloth, with a pattern of long-tailed birds in yellow thread on the back cushions, and I stand looking at them, until Tina comes back.

“Don't just stand there,” Tina says. She comes close, so I put my arms out and around her and she leans into me for a moment, releasing her weight, as if all the heaviness of the world had been pressing down on her from the sky, urging her without relenting into the rest that I am, her softened flesh running to thickness around the waist and warm and pillowed where her breasts push against my chest. “Rest here for a minute,” Tina / rest is better than sleep, because asleep you don't know you are resting, and the best is the early morning still dark in the window but the first light then nudging slowly as if in increments though it is not incremental, the light over the edge of everything wedging into the dark until gray sky and then blue sky and then colors among the things down here, and the smell of coffee, and sitting so that my hip eases from the night of lying on it, the easing of the ache a pleasure, and greater pleasure in being alone for half an hour between my waking and tammy's, though pleasure later in being with her, too, both of us far away and alone together, love for her but also a dullness in that, an incapacity and fear, but away from people loud hot smelling crowd men pushing in always with their eyes and their hands moving, and jesus i am a whore, how the fuck did that happen?, but tammy will be up soon and she can't understand no hot water, must wait until there is the money, a whore, but remember my mommy's shining red shoes with little straps over the toes and the heels so steep i held the porch rail almost falling but walked the shoes too big slipping and mommy laughing happy in the doorway, tina tina you beauty someday you will know what shoes like that are for, but not tammy, but now this boy big clumsy dumb oh jesus what an idea, but only a few minutes and then / says, except that I am not rest now, I am chaos before there were names, and her scent enters me, shampoo and the perfume almost as thick as lather on her skin because it is supposed to disguise the odors of cigarette smoke and sweat but does not disguise anything, and under that the woman smell that is really her, as warm and pulsive as crumbled bread or the smell of black wet earth that drips from the harrow blades before seedtime. I don't want her to move away, but she shifts her weight back into her bones and stands, tugging at my belt and slipping the button of my pants loose. She pushes in the middle of my chest and says, “Sit here,” and I sit on the old couch. Tina on her knees drags my pants down to my ankles.

I am Calf's mother in her mouth, and she is Calf.

But I don't understand how the time splits and jumps, and there is too much stretched-thin red noise inside me, and I am falling down the metal stairs outside. I try to catch myself, but my wrist hits the handrail hard, so that my arm rings and vibrates like the metal, and I am still falling, and I go over the rail out into the black air. I fall for a long time and land on my back, and the frozen ground knocks the air in my chest into a ball that hurts to push up through my throat, and I turn over with my knees up to my belly, looking for a way to breathe. Tina clatters down the stairs, shouting, “Jesus, are you okay? Are you okay?”

“What the fuck did you do to him?” Dad roars, standing over me, and Tina flinches away from him and says, “Nothing nothing, he just got up and ran, I don't know — nothing!” afraid and close to crying. I can breathe now, the air like thin oil on the inside walls of my chest, and Dad gets down on his knees and feels my arms and legs to see if bones are broken. He asks if I am hurt.

“No,” I say.

“Can you stand up?”

“Kay.” Dad tries to help me up, but the wrist he is holding hurts like pouring ice water on it, and I fall back and then stand by myself, holding my hand against my side.

“He ought to go to the emergency room,” Tina says, then, “But you take him there, okay? Don't bring no ambulance here. What the fuck, Kyle? Why did you do that?” She is shaking. Her voice / fuck why did he do that? I can't be in trouble again I can't. He's hurt but fuck fuck / shakes apart in the air, into thin strings of sound that blow away.

Dad holds my other arm and leads me back to the truck in small steps like an old man. My face is wet. Crying smells warm. He left my red car on the table. Calf, I think, and I feel mean because I haven't thought of him for a while, and he seems smaller because I have not been thinking about him. Before he was born, I could put my face against his mama's side and feel Calf moving inside her, but he must be sad now because she is so far away, no longer her hot blood frothing and humming through the channels of her and all around him as he waited long in the cage of her ribs, before ever the first waking, as she knitted him bone and hair and eye, particle after particle, from the nothingness where he was not.

“Shhh,” Dad whispers, “shhh, Kyle, you're okay, we'll go to the doctor, and you're okay.” Then my feet are far away and my legs are wobbly liquid. I can't find the ground, and I fall over an edge again into another dark. For a long time I try to move in the dark, but I can't move, then I wake up.

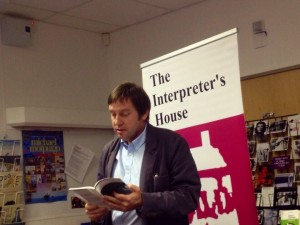

James Owens's most recent collection of poems is Mortalia (FutureCycle Press, 2015). His poems and stories have appeared in Blue Fifth Review, Poetry Ireland, Kestrel, Appalachian Heritage, and Kentucky Review, among others. Originally from Southwest Virginia, he worked on regional newspapers before earning an MFA at the University of Alabama. He now lives in central Indiana and northern Ontario.

James Owens's most recent collection of poems is Mortalia (FutureCycle Press, 2015). His poems and stories have appeared in Blue Fifth Review, Poetry Ireland, Kestrel, Appalachian Heritage, and Kentucky Review, among others. Originally from Southwest Virginia, he worked on regional newspapers before earning an MFA at the University of Alabama. He now lives in central Indiana and northern Ontario.