The closer it got to Joey’s dad’s birthday, the more agitated he became, and with nothing worthwhile to do when he wasn’t at work – which was less and less often since Jerry had been cutting his hours – he spent his time lifting weights. So when Chyna rolled in, middle of the night, and flashed a letter postmarked from Texas with his and Chyna’s names on it, he wanted no part of it.

“It’s nothing bad, I’m sure,” she said. “Probably saying he’s sorry he missed your birthdays and isn’t around.” She smelled like perfume and Marlboro Lights and took a long drag on a Route 44 Cherry Dr. Pepper from Sonic.

“Shouldn’t be in prison, then,” Joey said, glaring at the TV.

Chyna didn’t answer that; she just started in from the top, reading it to Joey while he sulled but listened – he wasn’t far enough gone in his anger to ignore his fealty to his sister.

The letter started, like she’d predicted, with apologies, and then moved to questions. It asked about Joey’s life, how he was doing in school, whether he was doing anything stupid.

“How’d he get our address?”

“He used to live here, stupid,” she said. “And I wrote to him.”

Joey was stunned. “Why in hell would you do that?”

“He’s our father.” Her voice was soft, vulnerable.

“Is he?”

She continued reading. Joey’s anger caused him to miss the immediate bits that followed, but he tuned back in as his father, apparently in answer to a question of Chyna’s, described his life.

“It’s boring here; that’s the main thing. You can read or play cards or something, but it’s the same every day. There’s some real hard fellers here, but long as you got friends, you’ll do all right. The food is no good, but you get used to it. I ain’t never been messed with, to answer your question. What I miss most is seeing you two and your momma and not being in prison.”

“You asked him if he’d ever been messed with?” Joey said.

“I was curious.”

He went on to describe his cell and his daily routine, as per Chyna’s questions.

“I got old, here,” he said. The implication was that he shouldn’t have.

Joey could picture it as she read; the narrow cell, the exercise yard. The images in his head were colored by movies he’d seen: Brubaker, with its death row that was little more than a series of boxes; Robert Redford digging hole after hole. He saw his father as the vague memory he had; a bone-thin frame, taut with muscle. The man in Joey’s head was always tan and grinning. He probably wouldn’t be tan anymore, Joey figured. And he sure as hell wouldn’t be smiling.

“I’m going to write him back,” Chyna said, breaking Joey’s reverie. “Want me to say anything?”

Joey considered it. “Tell him not to worry about not being here. I don’t miss him.”

* * *

Joey didn’t see Tommy standing in the doorway watching him work out, though Joey had worked himself into such a state of exhaustion, he could barely register what was right in front of him. Joey finished his rep. and sat up on the weight bench.

“You training for something?” Tommy barked.

“No sir,” Joey said. He wiped sweat off with a threadbare towel.

“Come on and make a run with me.”

“Can I take a shower first?”

“I’d rather you did.”

They drove out by the municipal airport, in the tangle of barely graveled roads, pulled off into a grotto Joey’d never known existed. Tommy killed the engine and pulled up to a trailer hidden amongst some weeds.

“Don’t say a fucking word,” Tommy said.

They got out and Tommy handed Joey a duffle bag from the trunk. They went to the door and stood there without knocking. Joey heard footsteps moving through the brush, and somebody came around the side of the trailer, but all Joey could make out was the twin barrels of a shotgun amongst leaves.

Tommy grabbed the bag and set it down by the trailer door. He stepped back and Joey went with him. Another bag flopped by their feet. Tommy nudged Joey who picked it up. They went back to the car, Tommy cranked it and revved it a few times, and backed out all the way back to the road before turning around.

“Know what’d happen if you knocked on that door?” Tommy asked.

“Double-dog dare me,” Joey said.

Tommy laughed a little. “Hungry,” he said and they went into town for something to eat.

* * *

After that, Tommy was bringing him along all the time.

“You don’t ever ask nobody their name,” Tommy said. “Don’t ask no questions or they’ll think you’re a narc.”

Joey took it all in. At first, it was mostly just him riding along. A couple times, Tommy took Joey with on longer trips; they’d end up trading joints in some tweaker’s house while he read from the bible about the end of the world, eating can after can of baked beans; or, they’d stand in some guy’s kitchen while his battered-looking wife chased around kids who already talked back to her because they saw their daddy do it, trading shots. It was like that, Joey realized; you had to spend time with them. His experiences with pot smokers had been the same, but he’d thought they were just lonely losers; turned out, you had to put in time, let them get to know you, or they got suspicious.

“Anything happens to him,” Joey’s mom, KT, said after one trip. “I’ll never forgive you.”

“I know,” Tommy said, a simple statement of fact.

Joey had known his mom and Tommy sold weed and sometimes meth for years; people were always coming by, or Tommy was always off on some errand for days at a time. Joey had assumed it was mostly weed they were selling, and maybe it had been, but these days, Tommy seemed to want to step it up. He didn’t offer an explanation, and Joey knew better than to ask for one.

It was surreal for Joey – one minute, he’d be out in the sticks shooting cans for target practice with some guy who’d just as soon stick an ice pick through Joey’s eye as see him, and the next, Tommy would drop him off at school, and Joey would be sitting in some class trying not to fall asleep. He smoked plenty of pot and drank, but Tommy only let him try meth one time – Joey was pretty sure it was because of KT. But this one time, they’d been out at a dealer’s house, and he’d insisted that Joey join them in sampling the wares. Tommy tried to make a joke about it, but the guy got wide-eyed and weird, so Joey had to do it. Tommy kept eying him as Joey lit the pipe like he’d seen so many others do and hit it.

It was kind of the opposite of pot; whereas marijuana made Joey feel spacy and distant, meth made him feel present, very fucking present, and clear-headed in a deceptive way.

He didn’t sleep the next day, or the one after that. He stayed out with Tommy, and when he was finally made to go to school, he cut classes and jogged around the school, grinding his teeth and working out weird theories in his head. When he finally crashed, he slept a solid day and a half.

From time to time, the old guys would stare at Joey for a while and then get this knowing look on their faces. The first time it’d happened, Joey thought he was about to get raped. But then the guy had pointed at him and asked his name. Then he’d started talking about Joey’s dad.

As far as Joey knew, his dad ran guns. Some of KT’s oldest friends would reference him, but they hardly ever came to the house. The weird thing about them was when they did, they’d actually talk to Joey and Chyna, back when she was around, anyway. They’d ask how the kids were doing in school, the standard bullshit. Joey’d asked Chyna about it one time, and she’d explained they were friends of Joey’s dad. He didn’t know how to feel about it.

But the way these guys talked, it was like Joey’s dad was a legend, instead of some guy rotting in a Texas prison. They’d tell stories about fights he’d gotten into, people he’d screwed over or who tried to screw him over. Joey had never really thought of him as a person, but here he was, living on in the tattered memories of a bunch of tweakers.

After they’d left that one’s house, Tommy had been antsy in the car.

“You remember your dad?” he asked.

“Not really,” Joey said.

Tommy grunted. “Good man,” he said, which shocked Joey.

“You knew him?”

Tommy laughed. “We came up together. He was always smart, smarter than me.” It was the most he’d ever really heard Tommy say.

“Were you friends?”

Tommy grunted. “He told me to take care of you and your momma,” he finally said. Joey sat, stunned, the rest of the ride home. He wanted to ask Tommy questions, but couldn’t think of a one. Later, as he lay abed, trying to sleep, he made a list in his head that he knew he’d never ask:

1. If he was smart, why was he in prison?

2. Does he know you’re fucking his wife?

3. Did you run guns with him?

4. What’s the difference between manslaughter and murder?

* * *

Joey was upstairs, working out again. This time, it was his mom standing in the doorway when he looked up.

“Know what today is,” she said.

“Tuesday,” Joey said, wiping himself off and starting in on curls.

She came in and sat on the bed. “Chyna’s been writing to him. Said he wrote to you.” Joey didn’t answer. “Wrote to me, too.” She let it slip out so he could’ve ignored it, but it hit him like a slap to the face.

“What’d he say?” Joey said, trying to sound nonchalant.

“Said to make sure you don’t end up like him.”

Joey laughed. “In prison?”

“Selling.” Again, it was a simple statement that carried massive weight.

“Talk to Tommy. He’s the one always taking me along.”

“I have. Way he figures it, and I don’t disagree, is you want to do it.”

“I guess I’m learning a thing or two.”

“I guess you are.” Joey switched arms and started curling with that one as she continued. “You don’t have to, though.”

“What else am I going to do?”

She nodded and rose but didn’t leave.

“Does it bother you? That you’re out and he’s not?” He didn’t make eye contact, just let it lie.

“It does,” she said. “But he forgave me. I did what I had to do for you kids.”

Joey thought of a few things to add to that, but he let it go and focused on his exercises. A moment later he felt a cool hand on his shoulder and looked up into his mother’s sunken eyes. Her face was wrinkled, the skin slack. She was nearly toothless, though her hair still had traces of black amongst the gray. There was a squirreliness about her eyes, but in the centers, they were calm. She smiled and he did his best to soften his face.

* * *

Joey rode to school with Chyna when Tommy didn’t drop him off. And almost every day, he rode home with her.

“Come and go for a ride with me,” she said when he met her at her car.

“Yeah, I was going to.”

“No, I mean…just get in, dumbass.”

She took him up Rabbit Road and turned off east on the somewhat paved road that took them, eventually, out to the municipal airport and the tangle of gravel roads that circled it.

“Clint asked me to marry me,” she said, apropos of nothing.

Joey laughed before he could stop himself and she reached over and smacked him, hard.

“Sorry,” Joey said. “So what did you say?”

“I told him I’d think about it.”

Joey looked at her. “Yeah? And what did you think?”

She shrugged, which was a little troubling, because she had this way of lying on the wheel and steering with her shoulders, so when she shrugged, the car veered to the side.

“Really?”

“Yeah, I mean, I really like Clint.”

Joey looked straight ahead. “Why?” He finally asked.

She punched him again. “Nevermind.”

“No, I’m serious. Why do you like him so much?”

She glared at him until she realized he was being serious and then slackened up. “I don’t know. He’s nice. He respects me.”

“Does he?”

“More than Tommy and KT.”

“Okay. So what do you get out of marrying him? I mean, what does that do for you?”

“Not everything is about what you can get out of somebody.” Joey didn’t answer. He settled back into the seat and watched the trailers and trees move by. “You can come visit,” she added.

He laughed again. “I’m doing okay.”

She looked at him. “You’ve been going out with Tommy. KT told me.”

He shrugged. “Got to learn a trade.”

It was her turn to laugh. “So you can end up like dad?”

“Least I won’t be leaving a family behind. But at least I can count on you to write me letters.”

* * *

Joey was on a run with Tommy, hanging out at the house of a guy they’d dealt with a couple times, just drinking beers and bullshitting, when the phone rang. The guy’s wife answered and then turned to the tweaker.

“Billy, they’re asking for somebody named Tommy.”

Tommy and Joey both looked up like that cat that had caught the canary.

“You give somebody this number?” The guy asked.

“Hell, I don’t even know this number,” Tommy said.

The guy took the phone and demanded to know who it was, but clearly wasn’t getting anywhere.

“Hell, it’s for you,” he said and handed it to Tommy. “Won’t tell me shit.”

“Yeah?” Tommy said. He had a confused look on his face and didn’t speak again except to say. “Yeah, I get it.” Then he hung up and went back over by Joey.

“Well? Who was it?”

“Wrong number,” Tommy said, pulling on his beer.

The tweaker looked at him, mean as a snake, and then laughed loud. They talked some more, and about five minutes later, there was a knock on the door. The wife went and answered it and cried out as someone shoved her aside. Joey didn’t realize Tommy wasn’t beside him anymore until he saw him wrestling with the tweaker, who was trying to pull out a handgun from a drawer by the sink. There were two guys at the door, and they beelined for Tommy. One of them hit the tweaker’s hand hard, which was half in the drawer, and he yelped. Tommy stepped out of the way, hands raised, while the two took the tweaker to the door. His wife was on the floor, and one of them knelt and helped her up.

“We’re sorry, Darla,” he said.

“Yeah, just call me and tell me where to get what’s left of him.”

They closed the door behind them.

“Want us to wait with you?” Tommy asked.

She sat at the kitchen table. “Yeah, hell, y’all hungry? I got some squirrel and dumplings.”

“Shit yeah,” Tommy said.

While she was heating it up in a big pot on the stove, Joey nudged Tommy.

“What did they say on the phone?”

“Said somebody’s going to come knock on the door and ask for Jack. Said to let them take him, otherwise, they take everybody.”

“Did you know who it was?”

“If I did, I don’t want to.”

They each finished two helpings of squirrel and dumplings with some cats-head biscuits on the side before the phone rang. Tommy looked over at Darla, and she gave a ‘go ahead’ motion. He answered and said, “All right.” And hung up.

“Said we can pick him up at Big Eddy Bridge. Want us to go get him?”

“I got the kids coming in from school any minute,” Darla said.

When they drove out, they found him in the middle of the concrete, bruised and bloody. They were halfway back to town before they realized he was missing a finger.

“What did you do?” Tommy asked.

But he kept screaming until they dropped him off at the emergency room.

“Must’ve owed somebody money,” Tommy said.

* * *

After they went home, Joey went up to his room and thought about everything and then went and knocked on KT and Tommy’s bedroom door. Tommy hollered from inside, and Joey told him that he wanted to talk. There was a lot of grumbling before Tommy opened the door.

“What in hell do you want?”

“I want to do more, sir.”

“Well clean the damn house, then.”

“No, with the…you know…what we’ve been doing.”

“Shit.” Tommy shook his head and turned and slammed the door behind him.

* * *

Chyna graduated, and Joey was surprised when KT and Tommy actually showed up for it and sat beside KT’s mother awkwardly.

“I’m surprised you graduated,” the kids’ grandmother said to Chyna. She turned to Joey. “Think you can hold out two more years?”

“Yes ma’am,” Joey said because it was what she wanted to hear.

Clint came with them when they went out for dinner at The Catfish Hole restaurant, on Grandmother’s dime, of course. She nibbled on one piece of fish while the rest of them gulped down hushpuppies, French fries, and piece after piece of fried catfish. Tommy burped loudly and pushed his plate away, knocking over his sweet tea, which deepened Grandmother’s scowl.

Chyna cleared her throat. “Clint asked me to marry him,” she said, glancing at him. He smiled and took her hand.

“You knocked up?” Tommy asked.

Grandmother gasped.

“No,” Chyna said. “Don’t be a pig.”

Tommy eyed Clint. “You whipped or something?”

Clint shook his head slowly. “No sir. I love Chyna.”

Tommy grinned, and KT elbowed him hard.

“And what do you do for a living, young man?” Grandmother asked.

He explained his work for a propane company. It wasn’t that interesting, so Joey and Tommy both zoned out. They both tuned in when Grandmother laughed at something Clint had said.

“He’s quit a catch, Chyna,” she added. Chyna squeezed Clint’s hand. Tommy and Joey exchanged looks, frankly too shocked to respond.

The plan was that the couple would move to a house Clint’s grandparents had lived in

a little town called Shirley up in the mountains to the center of the state.

“Shirley?” KT said. “Who’s she?”

Joey rode up with Chyna and Clint to help her get moved in that weekend, trying not to flinch when Clint raced up the hills and around the tight curves. When they got to the town, he wasn’t impressed.

“Hell, ain’t nothing here but bears and a Sonic,” Joey said.

Clint laughed. “You’re not far wrong.”

The thing that annoyed Joey about Clint was that he was all right. After they unloaded Clint’s truck, he took Chyna and Joey to Sonic for lunch. They drove back that afternoon with an air of easy camaraderie.

When they dropped Joey off at the house, there was a letter from Joey’s dad lying on his pillow.

* * *

Joey stared at it for a few seconds and then sat on his bed and ignored it for a few more. He started for the door to go downstairs, but he was tired from the heady day and caught himself. He grabbed the letter and ripped it open and scanned it.

“They set a date,” it began. “I’m out of appeals.” The tone was sober with a couple of attempted jokes, even. “I’d like you to be here, since you’re my son,” he said. “But I understand if you can’t.”

He read the letter over three or four times and dropped it. He could hear a hum of music downstairs from KT and Tommy’s room. He went back over to the doorjamb and punched the wood, hard. Then again. Then again until his hand, not the wood, splintered. He went back downstairs and knocked on his mom’s bedroom door with his left hand. When she opened it, he held up the already swelling hand.

* * *

“I’m not going,” Joey said. He was on the phone with Chyna, pacing across the scuffed linoleum in the kitchen.

“He asked,” Chyna said. “It’s his last request.”

“So?” Joey said. “Hell, he doesn’t even know who I am. I could send somebody else, and he wouldn’t know.”

Chyna didn’t answer that. “I would go,” she finally said.

“So go.”

“He asked you.”

“Oh well.”

“You know,” Chyna said. “If you hate him that much, you should go just to see him fry.”

Joey didn’t have an answer for that. They ended the call soon after, each agitated, though without a specific focus for it. He went up to his room, closed the door, and went over to the bookcase against the wall beside the door, squatted down, and pulled the bottom out. He paused and listened, and when he was satisfied, he reached in and dug out a cigar box and sat with his back against the door. Inside, there was a letter and a photograph and some other trinkets. The letter was dated about five years ago. The paper of the envelope had gone yellow, and the letter inside as well. He opened it carefully, being especially gentle with the folds, which were tearing on the edges. He read over it and then folded it and put it back in the envelope. The picture was of a man holding a baby. For the first time, he could see himself in the man’s face. He stared at it a long time and then put it back with the letter. There were other things – a baseball card he’d thought would be valuable someday, some little toys he’d held onto for some reason.

He put it all back in the box, added this new letter to it, and put the box back under the bookcase and pushed it back against the wall. The letter had said it would happen over the summer. Joey didn’t know why it was such short notice; maybe his dad couldn’t decide to send the letter.

* * *

Tommy drove out to the house of the tweaker they’d taken to the hospital just a couple weeks before.

“You going to Texas?” Tommy asked.

“I don’t think so,” Joey said.

Tommy made a noise. “Why not?” He finally said.

Joey shrugged. “Why would I?”

“He’s going to be dead forever. He’s only going to be alive a little while longer. You can hate him as long as you want, but this is your only time to see him,” Tommy said.

Joey was stunned silent as they pulled up to the house and got out. Tommy went and banged on the door and grunted something, and Darla, the wife, opened it and let them in. Joey noticed she wouldn’t look them in the eye, but he was so focused on other things, he wasn’t really paying attention.

Billy, the tweaker, was out back in his shed, apparently. Darla led them through the house and pointed them to a squat, square building still showing its insulation. Tommy glanced back at the house, which caused Joey to. The glass door was closed behind him.

“Run and try that, quiet-like,” Tommy said.

Joey tried the door and showed Tommy that it was locked. Darla had pulled the blinds closed as well.

“All right,” Tommy said. “Something’s up. He’s watching us, I figure.”

He knocked on the door.

“Come in,” Billy said.

Tommy nodded to the side and Joey stepped clear of the door. Tommy pushed it open and stepped to his left a moment later, lingering in the doorway just a second. A gunshot rang out. Tommy pulled his handgun out and ran to the side just as a shot blasted through the wall where he’d been. Joey high-tailed it the other way. Tommy found a window and peeked in. He glanced at Joey, who was lying on the ground about fifteen feet away, strode up to the window, and fired several times, then ducked back away from the wall. There was no answering shots, but a sound from the house made them both turn. Darla came busting out, screaming, shotgun in hand, running for Tommy. She didn’t make it, because Joey tackled her before she’d covered half the lawn. Tommy disappeared into the shed, and one shot rang out. Joey rose and trained the shotgun on Darla, who got to her feet and crossed her arms. Tommy emerged a moment later.

“Where is it?” he asked. Darla just sneered. He slapped her, good, across the face, and she fell to the grass.

“It’s gone!” she said. “He smoked it all! Why do you think he did this?”

Tommy put his gun to her forehead. She looked scared but didn’t cry until he took it away.

“When you tell the pigs about who did this, you want to think about that boy in there. Think real good, you hear?”

“I hear you,” she said, on her knees.

Tommy went back into the house. Joey followed, still holding the shotgun.

* * *

After that, the business dried up for a while. The familiar smell of weed began emanating from Tommy and KT’s bedroom. The week of the execution came, and Joey was spending much of his time in his room when Chyna came to visit. She tapped on the door. When Joey didn’t answer, she pushed it open. He was on the floor, sketching.

“You haven’t drawn in a long time,” she said.

He looked up at her. “What are you doing here?”

She shrugged. “Visiting. Can I see?”

He passed one up to her. She studied it. “You doing superheroes again?”

“It’s from a dream I had,” he said.

She carried it over to the bed. “Tell me about it.”

He sat up on his elbows and related the dream, all about an alien planet or maybe it was in the future after society collapsed. There were these warriors who jousted but with cars. That’s what he was drawing.

“Cool. Did you do any more?”

He showed her a couple others he’d done of the jousters and a protagonist he hadn’t worked out a story for.

She set them on the bed, and he kept drawing. “So it’s tomorrow,” she said, after a while. He didn’t answer. “I was thinking of driving down.” Still, the only answer he gave was the scratch of pencil on paper. “So you wanna ride down with me?” He paused, but still didn’t speak.

“I don’t want to see it,” he said and kept sketching.

“You don’t have to. Just ride with me.”

He finished and set the pencil down. “First time I would have seen him in ten years would be when he dies.”

“Just ride along so I have somebody to talk to,” she said.

He sighed and shook his head.

* * *

They left that afternoon after Joey packed some clothes, pencils, and paper. The plan was to drive it in one day, crash in a cheap motel, and Joey would hang out while Chyna went to the thing. They joked and listened to music and made fun of signs the way they used to, before things got tough; Joey started to feel like himself again.

That night, in the motel, they ate pizza and didn’t even turn on the TV. Joey woke in the middle of the night when Chyna threw a shoe at him to make him stop snoring, but even that felt right to Joey. The next morning, she asked if he would go with her. He’d known she would but hoped he was wrong.

“I don’t want to see it,” he said.

“Because you hate him or because you’re afraid you don’t hate him?” she asked. When he didn’t answer, she added, “It’s a chance to see someone die.”

“I’ve already seen that,” he said. He told her about the tweaker.

“Oh Joey,” Chyna said and grabbed him in a hug. Somehow, he ended up in the car trying to think of excuses not to get out all the way to the prison.

There were a handful of protestors outside, which really shocked him. When Chyna parked, he hopped out and went over to them, with her following and trying to stop him.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

An elderly nun with sad eyes explained that they were protesting the death penalty.

“That’s my father in there,” he said.

“I’m so sorry, my son,” she said.

“He killed 37 people.” She just stared for a moment. “But it was manslaughter not murder because he was just involved in the killing. Like he helped other people kill. They couldn’t pin them all on him.”

“Come on, Joey,” Chyna said.

“It must be hard having a man like that for a father,” the woman said. The other protestors were gathering around him and her, now.

Joey shrugged. “He’s been in prison most of my life, I guess.”

The woman patted him on the arm and called out, “This boy is the son of Lucas Newcarter!” People started noticing, then. “How can you murder this man while his son watches?”

“No,” Joey said. “He should die. He’s a bad man!”

“They’re making an orphan! Will that bring back the dead?”

Chyna dragged Joey away to the building. “Bitch,” she said.

A man guided them to metal folding seats in a little room facing a big window. There were a couple other people there, but not many.

“You know, I think you were right,” Chyna said. “He made his bed, and he has to lie in it.”

They brought him out and led him to the chair. It was kind of far away, but he saw them and smiled a little. Joey smiled back, purely by instinct. They put him in the chair and strapped him in, said some words, and pulled a big elaborate switch, and he was dead.

“Well,” Chyna said, “I guess that’s it.”

But Joey was crying, hard. He didn’t know why and he didn’t know how to stop.

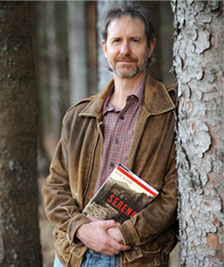

CL Bledsoe is the author of five novels including the young adult novel Sunlight, the novels Last Stand in Zombietown and $7.50/hr + Curses; four poetry collections: Riceland, _____(Want/Need), Anthem, and Leap Year; and a short story collection called Naming the Animals. A poetry chapbook, Goodbye to Noise, is available online at www.righthandpointing.com/bledsoe. Another, The Man Who Killed Himself in My Bathroom, is available at http://tenpagespress.wordpress.com/2011/08/01/the-man-who-killed-himself-in-my-bathroom-by-cl-bledsoe/. He’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize 10 times, had 2 stories selected as Notable Stories by Story South's Million Writers Award and 2 others nominated, and has been nominated for Best of the Net twice. He’s also had a flash story selected for the long list of Wigleaf’s 50 Best Flash Stories award. He blogs at Murder Your Darlings, http://clbledsoe.blogspot.com. Bledsoe reviews regularly for Rain Taxi, Coal Hill Review, Prick of the Spindle, Monkey Bicycle, Book Slut, The Hollins Critic, The Arkansas Review, American Book Review, The Pedestal Magazine, and elsewhere. Bledsoe lives with his wife and daughter in Maryland.

CL Bledsoe is the author of five novels including the young adult novel Sunlight, the novels Last Stand in Zombietown and $7.50/hr + Curses; four poetry collections: Riceland, _____(Want/Need), Anthem, and Leap Year; and a short story collection called Naming the Animals. A poetry chapbook, Goodbye to Noise, is available online at www.righthandpointing.com/bledsoe. Another, The Man Who Killed Himself in My Bathroom, is available at http://tenpagespress.wordpress.com/2011/08/01/the-man-who-killed-himself-in-my-bathroom-by-cl-bledsoe/. He’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize 10 times, had 2 stories selected as Notable Stories by Story South's Million Writers Award and 2 others nominated, and has been nominated for Best of the Net twice. He’s also had a flash story selected for the long list of Wigleaf’s 50 Best Flash Stories award. He blogs at Murder Your Darlings, http://clbledsoe.blogspot.com. Bledsoe reviews regularly for Rain Taxi, Coal Hill Review, Prick of the Spindle, Monkey Bicycle, Book Slut, The Hollins Critic, The Arkansas Review, American Book Review, The Pedestal Magazine, and elsewhere. Bledsoe lives with his wife and daughter in Maryland.