Bart Solarczyk lives In Pittsburgh, PA with his dog Pittie & cat Millie. His poems have recently appeared in Big Hammer, Roadside Raven Review & Pittsburgh Magazine. His book Tilted World is available from Low Ghost Press. Another collection, Classic Chapbooks, is available from RedHawk Publications & on Amazon.

Bart Solarczyk lives In Pittsburgh, PA with his dog Pittie & cat Millie. His poems have recently appeared in Big Hammer, Roadside Raven Review & Pittsburgh Magazine. His book Tilted World is available from Low Ghost Press. Another collection, Classic Chapbooks, is available from RedHawk Publications & on Amazon.April 5, 2022, 11:13 PM, prose by Bart Solarczyk

Bart Solarczyk lives In Pittsburgh, PA with his dog Pittie & cat Millie. His poems have recently appeared in Big Hammer, Roadside Raven Review & Pittsburgh Magazine. His book Tilted World is available from Low Ghost Press. Another collection, Classic Chapbooks, is available from RedHawk Publications & on Amazon.

Bart Solarczyk lives In Pittsburgh, PA with his dog Pittie & cat Millie. His poems have recently appeared in Big Hammer, Roadside Raven Review & Pittsburgh Magazine. His book Tilted World is available from Low Ghost Press. Another collection, Classic Chapbooks, is available from RedHawk Publications & on Amazon.Her Hotel, fiction by Timothy Gager

She bought a hotel, on the ocean, because God told her to. For this, she needed help, so she turned to God, and gofundme.com to raise ten million dollars for the purchase. She decorated her hotel with stars and starfish, or anything having to do with mariners, and the ocean, but mostly stars and starfish—-and thought, God is the stars.

Her hair was thick and curly, and hung down to mid-torso, both he loved to wash when they shared a tub. After he gently massaged in shampoo, he slowly poured water over her. The both shared this feeling of cleansing. Afterward, they would lay in bed in crisp sheets, the walls as glossed as a blinding light, looked at her ceiling, a flat blue-black, with specs of light painted on it. He drove up there the first three days of every month, as long as it wasn’t the weekend, as the hotel filled during those times. He said he was there because he loved the ocean, but didn’t worship it like a God, and he also let it slip that he loved her too.

Before the next month, she told him not to come. It was sudden, He represented too much of her old world and her spirituality demanded something which she could only describe to him, to make him understand, as something like their bath seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day, He tried a few times to get in touch with her, even calling the hotel’s office, but the recording only said that she/they were no longer taking phone calls but leave a message, if you felt called to do so, and would be returned if she/they were able and felt called to do so as well.

This all happened because there were things she never told him. It was a long story, which she had worked through, but it was important for her to be viewed as she was now, never as she was then. Before she was brought to the place she is in now, she used to work as a dental hygienist. She hated the early patients, first thing in the morning who rolled out of bed and did nothing to their mouths because they were getting brushed and flossed there. She hated the patients seen after lunch who only brushed twice a day, and not after lunch. They were the ones that left fish between their teeth. She had no respect for those who didn’t have self-care. Mostly it all came down to not brushing and flossing because if everyone brushed and flossed, she wouldn’t be needed as much.

The dentist who owned the practice became her lover. He was older, but not yet of the age where he smelled of being old. She liked how he ran the office, paying attention to her, and all the employees. He had empathy, and even commiserating about the morning and after lunch people she despised. The sex was great after hours, on a dentist chair, experimenting with the external oral suction machine, which she was responsible for the sanitizing of afterward. Then the sex was good at his house, and after she moved in the sex wasn’t as good. It became his way, and at his times. She also was stunned to realize he wasn’t at all the way he was in the office. He was unsupportive, critical, jealous of some of the patients she worked on, and verbally demanding and abusive. She no longer could stand him, but he was her employer, he was her home, and he had become her only lifeline, and he knew it. She felt an urge to do something bad enough to him to land herself in jail, or if she didn’t, land herself in an impatient facility.

The only way possible to leave him was mentally. As long as he thought she was coming on to patients she thought, why not graze her breasts against the back of the head of the men she from behind as she scaled his teeth? Why not whisper in their ear if they seemed responsive to that, about a place to meet later and a time? Why not give herself some sort of control? At first it seemed exciting, almost righteous, but often it brought her to another dark place where she wanted to take the sharp scaling tool and plunge in straight down through the next patient’s submandibular duct.

And then came the day, she and her dentist drove up the coast, and something was said, which she can’t remember, because he pushed her head hard against the passenger side window causing a concussion. She was in a hospital, and he was nowhere to be seen. When he did come back for her, the next day, she was gone, referred to a woman’s shelter on the ocean, run by a group of nuns known to be part of the Maryknoll Sisters. She loved the nuns, because of their presence of love, and that they gave her space to heal, and meditate and work her way out of her PTSD. She walked the beach, picking up shells, driftwood and dried starfish. The wood once important, had ended up here, exactly where she was, getting grounded in space. This was important, as the sand, the sea, and the stars, gave her peace.

She also began writing a book about overcoming her abuse, and broadcasting some of her story on the internet. The segments were heavy and touched on how she had been saved, and her rediscovered faith. She confessed she wanted to be a nun, a key revelation which would become the conclusion of her memoir. People followed her broadcasts, thousands of them, engrossed by her and her story. The nuns also tuned in. They liked her, but she wasn’t Catholic, and that was a reason good enough why she couldn’t become one of them. She would do the next best thing. She bought the hotel next door.

The hotel either had guests who loved the ocean, or guests who went there as an instrument of God’s teaching, based on her promotion. It was all fine with her, because she believed Gods was the stars, so why not it be the sea, or a man with a beard.

Occasionally she missed the man who used to visit, and wanted to have time with him, but then the thought made her feel uncomfortable and confused. She thought maybe it was fear, or perhaps love, but the one with the small “l”, not the big “L” which she lived for. She knew, without knowing her story, he couldn’t know her, and he could never be the One who knew the number of hairs on her head. She gave her story out to the world, but not to him, which represented something. The day she told him not to come back she already knew, he could never be He.

Timothy Gager has published 17 books of fiction and poetry. Joe the Salamander,is his third novel became an Amazon #1 Best Seller in its category. He hosted the successful Dire Literary Series in Cambridge, MA from 2001 to 2018, and started a weekly virtual series in 2020. He has had over 1000 works of fiction and poetry published, 17 nominated for the Pushcart Prize. His work also has been nominated for a Massachusetts Book Award, The Best of the Web, The Best Small Fictions Anthology and has been read on National Public Radio.

Timothy Gager has published 17 books of fiction and poetry. Joe the Salamander,is his third novel became an Amazon #1 Best Seller in its category. He hosted the successful Dire Literary Series in Cambridge, MA from 2001 to 2018, and started a weekly virtual series in 2020. He has had over 1000 works of fiction and poetry published, 17 nominated for the Pushcart Prize. His work also has been nominated for a Massachusetts Book Award, The Best of the Web, The Best Small Fictions Anthology and has been read on National Public Radio.

Fist Fight at Applebees, fiction by Dan Leach

I missed the beginning, but we know how it happens. Either the old man with the lazy eye said the wrong thing to the young man with the neck tattoo, or the other way around. I was there for the middle, and that’s the most important part because that’s when everyone’s still fighting like God’s in their corner. I can never tell whose corner God is in. I know this: the young man keeps dropping his hands, and the old man’s left is a hammer. There’s blood on both their faces. There’s a growing, happy crowd. Sometimes it seems like God’s in no one's corner. The losers down here have truth, but they’re hateful and inconsistent. The winners have status, but they use it for comfort, and comfort has ruined them. No one is humble. And isn’t God humble? Isn’t He gentle and open and lowly enough for anyone hurting? Okay, the fight. Someone got cracked. Someone’s head hit the pavement. The crowd screamed, and a child wept, but I was too far gone to see who won.

Dan Leach has published work in The New Orleans Review, Copper Nickel, and The Sun. He has two collections of short fiction: Floods and Fires (University of North Georgia, 2017) and Dead Mediums (Trident Press, 2022). An instructor of English at Charleston Southern University, he lives in the lowcountry of South Carolina with his wife and four kids.

Dan Leach has published work in The New Orleans Review, Copper Nickel, and The Sun. He has two collections of short fiction: Floods and Fires (University of North Georgia, 2017) and Dead Mediums (Trident Press, 2022). An instructor of English at Charleston Southern University, he lives in the lowcountry of South Carolina with his wife and four kids.

Everything is Relative, fiction by Michael Bracken

“Use my bed,” Zelda said. “I want to sleep in the wet spot.”

Alexandria stared at her younger sister for a moment and then grabbed my hand and led me upstairs to Zelda’s bedroom, where she attended to my needs with the lights off and her eyes closed.

My cousin and I had played doctor and gone skinny dipping together throughout our childhood, but nothing came of it until after Uncle Mort’s still exploded. The fireball instantly killed him, melted off half my face, and scarred a significant portion of my left side. Back then, my father was serving time for shooting a revenuer, and my mama and my Aunt Sara were working twelve-hour overnight shifts at the cotton mill. So, after I was released from the hospital, they left Alexandria to watch her little sister and care for me. And Alexandria did, taking advantage of my incapacitation to satisfy her curiosity about the sins of the flesh.

Afterward, as we lay in the dark without speaking, the doorbell rang. A moment later, Zelda yelled up the stairs. “It’s Goodwin.”

Alexandria’s boyfriend.

“Shit,” my cousin muttered. Then she yelled back, “Stall him.”

We quickly dressed. After I retrieved the prophylactic and its wrapper, Alexandria headed down the front stairs and I slipped down the back.

Zelda was standing by the kitchen door. She asked, “Is it wet?”

“Soaked.”

She smiled as she opened the door for me.

Outside, I shoved the prophylactic into the garbage can, careful not to make unnecessary noise. Then I climbed into the Ford my father and uncle had modified for running ’shine, released the parking brake, and rolled downhill in the dark until I was far enough away from Aunt Sarah’s house to safely turn on the lights, key the ignition, and drive home.

* * *

The next afternoon I took Zelda to town with me to do a little shopping. While people stared at me—or pretended not to stare at me—she pocketed a few items. The first time she did it, nearly a year after my release from the hospital, she took a chocolate bar, and it was half-melted by the time she pulled it from her underwear and showed me what she’d done. As Zelda grew older, we perfected our technique and now often left home with a shopping list. That day we shopped for eyeliner, earrings for Zelda’s newly pierced ears, and prophylactics for my time with Alexandria.

“Goodwin’s sweet on my sister,” Zelda told me on the way home. “He don’t know about you and her.”

“And you’d best not tell him,” I insisted. I didn’t know if what I was telling Zelda was for my own good or for Alexandria’s, but it didn’t matter. That Zelda knew about us at all was the result of her arriving home unexpectedly two years earlier. She caught me limping naked into their bathroom and Alexandria sprawled across her bed, and by then Zelda was old enough to understand what that meant.

Zelda didn’t respond to what I’d told her. Instead, she showed me the ten-pack of prophylactics she’d boosted from the drug store and said, “They’re ribbed.”

* * *

My only work experience had been helping Uncle Mort with the still, so my job prospects were limited when I was finally old enough to seek a real job. Martha Kukendahl hired me to wash dishes at the Roadside Inn, but she insisted I enter and exit through the restaurant’s kitchen door and that I never show my face in the dining room.

“Jedediah!” she said when I stepped through the back door a few days after my shopping trip with Zelda. “You’re late.”

I glanced at my watched. “Two minutes.”

“Third time this month,” she said. “If you weren’t Gladys Wright’s kid, I would have fired you already, you ugly little matchstick.”

I held my tongue because I needed the job, which I only had because Martha felt she owed my mama for something that happened when they were teenagers, something neither of them ever spoke about. With my father in prison, with my uncle in a grave, and without the money we’d once earned from their still, there just wasn’t enough money coming into the house to pay our bills without me working. Besides, Goodwin was Martha’s son.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “I’ll do better.”

The Roadside Inn did good business—a combination of locals and people traveling through—and I scrubbed dishware from the moment I arrived until well past closing time, when I helped Isaiah the Gimp clean the ovens and the stovetops and prepare the kitchen for breakfast the next morning.

I was near worn out by the time I arrived at Aunt Sarah’s house that evening, but Alexandria was waiting up for me. She took my hand and led me up the stairs to her bedroom, where she satisfied both our needs in near darkness.

“How do you do it?” I asked when she finished. “No one else even wants to look at me.”

“I close my eyes and remember how handsome you used to be,” Alexandria said. “Those other girls only see you as you are now.”

She didn’t realize how much her answer hurt, but I didn’t tell her.

* * *

The following Saturday, Zelda and I went to town again. This time the shopping list included feminine products and cold cream and socks to replace the pair I had worn though. I also needed to stop at the drugstore to pick up a prescription for my mama. While we were working our way through the Woolworth’s, a couple of girls from school saw us. They lived on the other side of the tracks, where the bankers and the mill owners lived, and they made rude comments under their breath, just loud enough for us to get the gist of their comments without hearing the actual words.

“They’re laughing at you,” Zelda said.

“They always do.”

“Do you ever think of other girls, Jed?” Zelda asked. “Girls other than my sister?”

“I used to, but who would have me?”

“You might be surprised.”

We left Woolworth’s with the three items on our shopping list and had to visit the drugstore for the last item. Afterward, we drove down to the river, hung our legs over the side of the bridge, and shared a Coke that Zelda had taken while I paid for my mama’s prescription.

“Things just ain’t been the same since Daddy’s still blew up,” she said.

We’d never talked about that day, about the explosion that had taken her father’s life and nearly taken mine, and about how our families had fallen on hard times without the money that still brought in. “And it ain’t ever going to be the same,” I said. “Some things are better. Some things ain’t.”

She pondered that for a bit.

“Daddy used to beat mama something awful,” Zelda said. My daddy had been the one who put a stop to it most times, but when he shot that revenuer and went to prison, there wasn’t anybody left who could stop what Uncle Mort was doing to Aunt Sarah.

Except God.

Or so we thought.

“You got your daddy’s car,” Zelda said. “You ever think of running ’shine for one of the other stills?”

“It’s been six years,” I said. I’d been fourteen and Zelda had been twelve. Since then, revenuers had shut down most of the stills, and the remaining few mostly provided small batches for local customers. “I don’t think there’s enough work for a driver.”

* * *

My mama and my aunt had to fend off the advances of the mill’s supervisors, ugly men who demanded personal favors, and they talked bad about the women who dropped to their knees in exchange for day shifts. They talked even worse about the husbands who turned a blind eye rather than jeopardize what was often their household’s only steady income.

“It ain’t worth it,” my mama told Aunt Sarah one night in our kitchen. I had stopped just outside the door to listen, something I did more often than they realized. “No matter what that man promised you, it ain’t worth it.”

“But I got two daughters,” Aunt Sarah said. “At least your boy can work, bring in some money.”

“Washing dishes,” my mama said. “That ain’t much of a job for a boy.”

“But it’s a job, a job he wouldn’t have if it weren’t for what you done for Martha all them years ago,” Aunt Sarah said. “It’s money ain’t coming into my house. We had enough money—more than enough money—before you—”

My mama hushed her. “You wasn’t okay with what Mort done to you, and Jimmy wasn’t around no more to stick up for you,” my mama said. “You be all right, just you wait and see. That Kukendahl boy, he’ll do right by Alexandria. I’ll see to that.”

I slipped away, not wanting to hear more about Goodwin and Alexandria. I knew he was sweet on her and that someday she would stop meeting my needs. But I surely didn’t need to listen to my mama and my aunt talk about it.

* * *

“Can I watch?” Zelda asked a few nights later.

We left the light on. Alexandria did things she didn’t usually do, as if she were performing for her little sister, and did it all without protection. We finished with her straddling me, and afterward, after Alexandria had left the bed and gone into the bathroom, Zelda crossed the room and let her fingers trace the scars on my face, an act more intimate than what her older sister and I had just done. When she finished, Zelda left me alone in her bedroom, listening to Alexandria shower, wondering what had just happened. I didn’t have much time to think because I soon heard a pounding on the front door, and Zelda called up the stairs to her sister, telling her she had a guest. I scrambled out of bed, grabbed my things, and hightailed it down the back stairs as quietly as I could.

I found Zelda waiting for me. She said, “You should see the look on your face.”

My face wasn’t all she could see. “Goodwin isn’t here, is he?”

My cousin shook her head.

“It isn’t funny,” I said. “What do you think’ll happen if he ever finds me here like this?”

“He won’t be none too happy.”

I pulled on my clothes. “What do you think will happen to your sister?”

Zelda shrugged. “She’d have to choose.”

I glared at her for a moment before stomping out of the house, climbing into the Ford, and leaving my cousins behind.

* * *

A few weeks later, my anger at Zelda had diminished enough that we took another shopping trip. At the grocery store she managed to tuck a couple of oranges into her bra, but the people at the drugstore had cottoned to our scheme. They watched her closer than they watched me, and I had to pay for the box of prophylactics I’d selected.

Afterward, we drove down to the river and hung our legs over the side of the bridge. We threw orange peels into the river far below and watched as the current sent them spinning away. We had almost finished when Zelda asked, “How come you never do this with Alexandria?”

“Do what?”

Zelda looked at me. “You know, take her places,” she said. “Like this.”

“Things ain’t like that with your sister. She don’t want me for that. She’s got Goodwin.”

“She just uses you for one thing.” Zelda stuffed an orange slice in her mouth and bit. Juice dribbled down her chin.

“I ain’t the only one being used,” I said.

Zelda put her hand on my thigh and looked at me in a way I’d never seen before. Uncomfortable, I threw the last of my orange into the river and pushed myself to my feet. “I need to get you home so I can go to work.”

* * *

After leaving Zelda at Aunt Sarah’s house, I continued on to mine. I needed to change shirts before I went to the restaurant, and when I came back downstairs, I heard my mama and her sister talking in the kitchen. They obviously didn’t know I was there, and I listened from outside the kitchen door.

“Your boy ain’t right,” Aunt Sarah said. “He ain’t been right since—”

“He wasn’t supposed to be there,” my mama said. “He was supposed to be in school.”

I had never stopped to wonder how my mama had reached the still so quickly after the explosion. That she was nearby because she had arranged for it to happen had never crossed my mind. I listened to her explain to Aunt Sarah how she had rigged the still, thinking it would blow Uncle Mort to kingdom come and nobody would be the wiser. She was getting back at him for what he had done to daddy and what he was still doing to his own family. When she found me half toasted by the explosion, she drove daddy’s Ford hell bent for leather down the mountain to the nearest hospital, where the doctors did their best to patch me up.

“I know you done it for me and the girls,” Aust Sarah said, “but it ain’t my fault you blew up your own kid.”

I couldn’t listen to any more. I didn’t want to listen to any more.

* * *

“You’re late again,” Martha Kukendahl said when I dragged into her restaurant an hour later, “and those dishes ain’t washing themselves.”

I glanced at the overflowing sink. I wasn’t thinking about work. I was thinking about what my aunt had said. I said, “No, ma’am, they ain’t.”

“Bad enough my boy is sweet on your cousin, I got to have you washing my dishes.” She crossed her arms and glared at me. “If it weren’t for your mama—”

“My mama? What’s my mama ever done for you?”

Martha grabbed my good arm and pulled me into the pantry where she kept all the dry goods. “You mama ain’t never told you what she done?”

“She don’t tell me nothing,” I said. “She hardly ever even looks at me.”

“Well, you ain’t nothing to look at, let me tell you.”

We stared at each other for a moment while she made up her mind.

“Twenty-five years ago your mama stole money from your grandpappy and bought me a bus ticket out of town,” she said. “I come back three years later with a baby, a wedding ring, and a story about a husband who died in a mine collapse.”

That made no sense to me. “Why would my mama buy you a bus ticket?”

“She didn’t do it for me,” Martha said, “She done it for your Aunt Sarah. She’s always done everything for your Aunt Sarah.”

I understood that. I’d lost half my face because my mama was protecting my Aunt Sarah.

“Twenty-five years ago your Uncle Mort—he weren’t your uncle then ’cause you wasn’t born yet—put me in a family way. He wouldn’t have nothing to do with me after ’cause he was sweet on your Aunt Sarah and I was just a drunken one-nighter.”

“My mama—?”

“She done it to keep your aunt from knowing what kind of man her husband was. Your Aunt Sarah knows what your mama done for me, but she don’t know why your mama done it.”

“That means Goodwin and Alexandria are—”

“Too damn close, but I can’t do nothing about that,” she said. “Now get your ass out there and wash them dishes.”

* * *

I scrubbed dishware until well past closing time. Then I helped Isaiah the Gimp clean the ovens and the stovetops and prepare the kitchen for breakfast the next morning. When we finished, I drove directly to Aunt Sarah’s house. I wanted to tell Alexandria and Zelda what I had learned, and I found my cousins sitting in the kitchen.

Zelda took one look at me and shook her head.

“We can’t do it no more,” Alexandria said as held up her left hand to show me a dime-store engagement ring. “Goodwin just left. I’m getting married.”

“Married?” I asked as I straddled a kitchen chair. “Why?”

“I’m pregnant.”

“Do you think it’s—?”

“Doesn’t matter,” my cousin insisted. “Goodwin thinks it’s his.”

Before I could say anything else, Alexandria left the kitchen and then left the house. A moment later, Zelda said, “I’ll take care of you.”

“But you’ve never—”

She smiled. “You’ll be my first,” she said, “and I won’t even close my eyes.”

I had so much to tell her, but maybe right then wasn’t the best time. She took my hand and led me upstairs.

Michael Bracken (CrimeFictionWriter.com) is the Edgar and Shamus Award-nominated author of 1,200-plus short stories published in The Best American Mystery Stories, The Best Mystery Stories of the Year, and elsewhere. He is also the editor of Black Cat Mystery Magazine and several anthologies, including Anthony Award-nominated The Eyes of Texas: Private Eyes from the Panhandle to the Piney Woods. He lives and writes in Texas.

FCAC reopened for YOUR submissions!

Yes, after a lengthy hiatus, FCAC will be posting content of interest from all corners of the rural hard boiled landscape again . Never fear for my other projects, Tough and LNP will continue apace; I just need the burst-wide feeling FCAC gave and continues to give me. Like, there's a gem of a story or two poems that just need a good place to live.

Yes, after a lengthy hiatus, FCAC will be posting content of interest from all corners of the rural hard boiled landscape again . Never fear for my other projects, Tough and LNP will continue apace; I just need the burst-wide feeling FCAC gave and continues to give me. Like, there's a gem of a story or two poems that just need a good place to live.

Hello People!

Tonight I was a force of nature. 1336 words in 1:15. First night like that in ages. I also had enough energy to clean out my cubbyhole of poetry. I discovered I can drink black coffee and be conscious for 16 hours without sleeping half the time away. I can promise the two were unrelated! All by cutting carbs. Of course my blood sugar was still sky high, and there was a near-constant background of almost-threatening voices, but still. It was a good day.

Tonight I was a force of nature. 1336 words in 1:15. First night like that in ages. I also had enough energy to clean out my cubbyhole of poetry. I discovered I can drink black coffee and be conscious for 16 hours without sleeping half the time away. I can promise the two were unrelated! All by cutting carbs. Of course my blood sugar was still sky high, and there was a near-constant background of almost-threatening voices, but still. It was a good day.

News of the Land

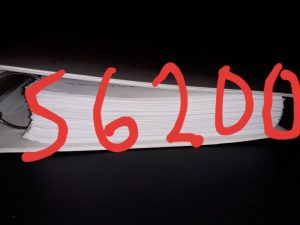

So yeah. About that novel. As many of mine do, this one topped out at 56K. I have not been able to hit the magical 80K-and-readily-agentable mark in some time, so it's likely, with edits and additions I have yet to enter, Comes the Flood will be around 60K, which will limit my submissions strategy somewhat. Still, I think it's a good book, or will be when I've polished the shit off its heels. I finished this novel in May. Since then the pandemic's gotten worse, I spent a month in a partial hospitalization and have slept the large part of those days in total withdrawal mode. Without the kids and Heather I don't know what I would have done. As a result, Tough fell behind and the lion's share of the reading load and all of the editing fell to Tim Hennessy, to whom I am eternally grateful. We're catching up and back to postiing stories, and will be adding three new staffers this week so we hopefully will never have to take time off again. I have a chapbook tentatively due out beginning of the year and I'm taking some time off from the novel to write some last poems for it. Here's hoping.

So yeah. About that novel. As many of mine do, this one topped out at 56K. I have not been able to hit the magical 80K-and-readily-agentable mark in some time, so it's likely, with edits and additions I have yet to enter, Comes the Flood will be around 60K, which will limit my submissions strategy somewhat. Still, I think it's a good book, or will be when I've polished the shit off its heels. I finished this novel in May. Since then the pandemic's gotten worse, I spent a month in a partial hospitalization and have slept the large part of those days in total withdrawal mode. Without the kids and Heather I don't know what I would have done. As a result, Tough fell behind and the lion's share of the reading load and all of the editing fell to Tim Hennessy, to whom I am eternally grateful. We're catching up and back to postiing stories, and will be adding three new staffers this week so we hopefully will never have to take time off again. I have a chapbook tentatively due out beginning of the year and I'm taking some time off from the novel to write some last poems for it. Here's hoping.

I keep buying books as if I'm going to read them, and I just haven't been able to keep up my usual pace, even with poetry. I'm going to top off this year at about eighty. Plans for next year include more reading, 150 books read, two written and completed novels, one of which will be the final book in the Ridgerunner trilogy. I'm getting my first tattoo. I'm 51 in a month. I'm tired of fucking around. Now if my brain just cooperates.

701

Tonight felt satisfactory. It wasn't a big fat adrenaline dump like last night's writing, but it went well. I could have written more, but I didn't want to leave it all in the page and flat-out exhaust myself either. A plot turn's come up though, and my outline is no longer viable for the second half of the thing, so tomorrow I'm drafting a new outline. I'm a little scared of doing it, frankly, since the writing's been going so well. I just need to stay vigilant, not let myself get a couple days out of sorts. So tomorrow there will likely be no update, as I'll be working on the outline all night tonight and most of tomorrow outside of my family commitments. It'll all be fine, right?

Tonight felt satisfactory. It wasn't a big fat adrenaline dump like last night's writing, but it went well. I could have written more, but I didn't want to leave it all in the page and flat-out exhaust myself either. A plot turn's come up though, and my outline is no longer viable for the second half of the thing, so tomorrow I'm drafting a new outline. I'm a little scared of doing it, frankly, since the writing's been going so well. I just need to stay vigilant, not let myself get a couple days out of sorts. So tomorrow there will likely be no update, as I'll be working on the outline all night tonight and most of tomorrow outside of my family commitments. It'll all be fine, right?

1147

On nights like this, there isn't much to say. Heather had half the day off so after mending fences from last night in the earlier part of her shift and because of being on the phone near-constantly in our new Covid-normal in the second half, I started writing much earlier than my normal 9:30 PM, and so by dinnertime now I've gotten my words in and may even be able to write again later on during my normal time.

I do have a normal time to write. 999 times out of a thousand, I'm writing at 9:30 PM every night, and I write until I get to 500 words within the hour or a thousand, or sometimes, rarely, more. More often than not when it's going well, I get a thousand words, so that's what I judge by: 500 minimum, the Graham Greene prescription, as described in The End of the Affair, but a thousand marking out a good strong day's writing. More than that, the Muses are smiling on me. Last night, a bad night that made me feel shitty until I sat down to write this afternoon, like a hangover. Tonight? Something else again. The only way through is forward.

I'm going to read now, and drink coffee, and maul a cat while I do. On deck, Cocaine and Blue Eyes, by Fred Zackel, Simple Justice by John Morgan Wilson and finally, Stoneburner, by William Gay. I'm halfway through the Zackel, a third through Simple Justice and I haven't begin Stoneburner yet, though I've owned it and started it a few times. I can already tell it's not top-notch Gay, but it's interesting, as the master's minutiae often are.

Edit in: 11:23 PM. Got an extra thousand words in for over 40K now. Halfway.

538

Not a good night. Rough on the family, rough on me with John Prine dying, just pandemic closeness rubbing everybody, well me, the wrong way. I didn't, couldn't write last night, and I'm in a shitty mood, so I'm counting these words as desperate and pleading with the muses to give me just a few more over the next month or so. And I want to apologize to my wife publicly for being such a prick. I'm sorry, baby. That's all. You all can call this the confessional blog.

It sucks sometimes, all the time, but most of the time you have to do the work anyway. But not always. Sometimes, like last night, I couldn't imagine doing it, and I'm paying for it in guilt all day anticipating when I can get to the keyboard and make it right, and words won't come, like tonight. Waah waah wahh. I didnt have to do it. I could stop. But I'm not going to.